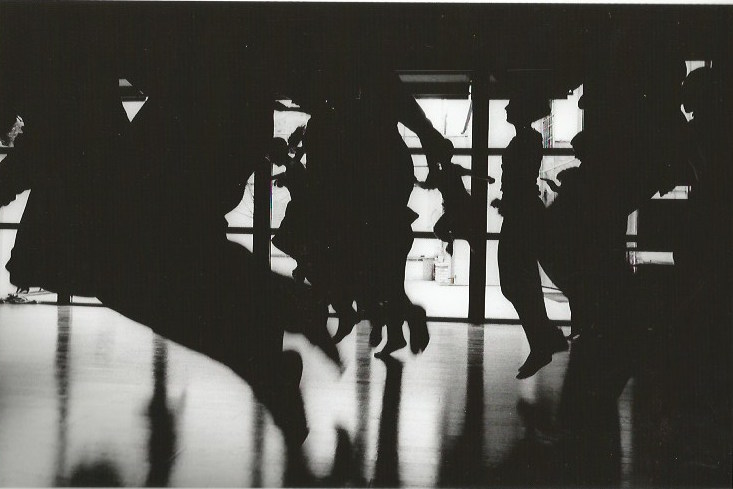

We interviewed Eva Blažíčková on the occasion of Duncan Centre Conservatory’s anniversary, as this year it opens its doors for the 25th time. Blažíčková’s life achievement was a result of a long-time effort which took a concrete form soon after the Velvet Revolution, in 1992. For me, personally (and I believe that I am not the only one) this conservatory is a place of great importance because it was right there Mrs Blažíčková managed to persuade me that dance had a solid position in today’s society and that it can have some impact on it, too. I rejoice in remembering the four-hour improvisations that made me touch the bottom of my physical strength, and, what is even more important, I discovered the wonderful world of dance with capital D, as Eva Blažíčková mentions in this interview. I would like to give her this intervew as a girf for her birthday she is celebrating today.

We interviewed Eva Blažíčková on the occasion of Duncan Centre Conservatory’s anniversary, as this year it opens its doors for the 25th time. Blažíčková’s life achievement was a result of a long-time effort which took a concrete form soon after the Velvet Revolution, in 1992. For me, personally (and I believe that I am not the only one) this conservatory is a place of great importance because it was right there Mrs Blažíčková managed to persuade me that dance had a solid position in today’s society and that it can have some impact on it, too. I rejoice in remembering the four-hour improvisations that made me touch the bottom of my physical strength, and, what is even more important, I discovered the wonderful world of dance with capital D, as Eva Blažíčková mentions in this interview. I would like to give her this intervew as a girf for her birthday she is celebrating today.This year “your” Duncan Centre Conservatory celebrates its 25th anniversary. But without you, it wouldn’t exist…Can you describe the circumstances of its foundation?

It all started in 1972, when my teacher and my great guru Jarmila Jeřábková handed her work to me, publicly. She devoted all her life to her work, despite the unfavourable circumstances. I witnessed the scene when some officials came to her private studio and put a sticker on her personal piano-forte saying: ‘Property of the District Cultural Centre’. So, she had to endure a lot and she did. At that time, I didn’t know what lay ahead of me (laughter). I was teaching regular classes in Jeřábková’s studio but after several years I found out I wanted to work with children much more. I took a job at an art school, so I could be with them more often and achieve better results in our artistic discipline. In the summer 1989 I was invited to join a group of international choreographers at the American Dance Festival. About twenty people from all around the world got together, it was a great experience, but also a negative one because of the terrible exposure to reality. What we were pushing to be included into art schools’ curricula in our country, what was criticised as absurd and lacking any technical basis, that was actually happening there.

Nobody seemed bothered talking about the centre of gravity of the human body, here it was considered a naughty word. It shocked me immensely. Suddenly I found out how much energy and effort had been devaluated by fighting human stupidity, emulation, and malice. So, I said to myself that I must have gone for it and started to plan a new private school. I was also teaching a group of children who pushed me to do it and they became the first students of the conservatory. When I finished my plans, I brought them to the ministry. It looks very simple now, but it took me two years of knocking at the bureaucratic doors, of explaining and persuading. After two years I succeeded, with the help from many influential people such as my friend, Dr Vladimír Justl, the then minister of culture Milan Lukeš, and also the director of the Department of Art Education, Dr Jaroslav Marek. He knew my work because I taught his daughter for a long time. At the end of the negotiations, Dr Marek said: ‘Do you really want to establish a private school, or you want it to be part of the system of state schools?’ That surprised me, and so I replied: “Let’s establish it as a state school, at least we can admit all talented children, not just the rich ones.” And so was founded Duncan Centre Conservatory in 1992.

One would say that the conservatory is your life opus, however you went even further and last year you established the Duncan Institute. Can you tell us something about it?

One would say that the conservatory is your life opus, however you went even further and last year you established the Duncan Institute. Can you tell us something about it?This action was preceded by almost twenty years as the head of the conservatory. I tried to promote the ideas of duncanism and I was happy that I could do so at a state school. Then came 2009, very successful year in all aspects. The school had been stabilised, its faculty was at a very high level and we completed a big project, Špalíček – it proved how much dance education is important for the development of children’s personalities because it affects a human being as a whole and forms it as a whole. Špalíček was very successful and I felt good and was ready to pass the school to the next generation in a good condition. I planned to stay as a kind of supervisor to be able to influence the situation at the conservatory. But as the past years brought many changes in the school management, I lost my chance.

And I simply left, I gave a notice at work…I don’t want to assist the ruining of my work. That is why I founded the Duncan Institute, so that we could do more research on what the legacy we protect means for today’s society, for current art and for the future, too. The Institute covers the activities that followed the school organically along its whole existence: The Society for Dance and Artistic Education that has for years organised the Festival of Progressive Personalities thanks to the dramaturgy of Lenka Flory (Lenka Flory is Eva Blažíčková’s daughter – editor’s note). The society oversaw putting the school into the context of the Western affairs. In the late 1990’s we opened the zero edition of Jarmila Jeřábková Award, a choreographic contest for young creators and dancers. The main mission was to give opportunity to the people from the countries of the former Eastern Bloc that functioned as Soviet satellites. We wanted to cast some light on the name of Jarmila Jeřábková who had showed huge courage under the communist dictatorship. The Institute is also an umbrella institution for a dance studio where we organise courses for people of all ages. We also have students over 60. It also shields a research room, archive, or a department that gathers historical documents I inherited from Mrs Jeřábková or that we retrieved from various sources.

What is your opinion on the current situation of art education and education in general?

What is your opinion on the current situation of art education and education in general?I think that the situation of the current education is not sustainable. The unbelievable poorness of mind, morals and humanity on the side of pupils as well as teachers, is mad. The assumptions that form the base of the education must be changed. It does not mean the change of the curriculum, but we must start discussing what education means for the society and how to structure it. And if we want to have a humane society, craft must be present. And this cannot be veiled by the talk of creativity, we touch the merit of things here. It will be a painful process, but we cannot avoid it because the system will fall apart anyway.

What does the idea of duncanism mean for you in current social context? Has the perception of this idea changed over time?

Yes, for sure. Teachers must absorb the impulses coming from their pupils, they must adjust the teaching to the contemporary views and still strictly preserve all qualities. It is necessary to change the way of transmitting the work so that it is acceptable for the current society. If I were a rigid duncanist, I would urge the children to dance in Greek chitons, which I find absurd. It is not about the formal, external side. The core is treating and preparing the physical side. We try to re-discover inside a human the lost natural principles and rules. Only through working with a body on such a basis can be created a solid support for thinking, intelligence, his emotional and spiritual life.

What does dance mean to you?

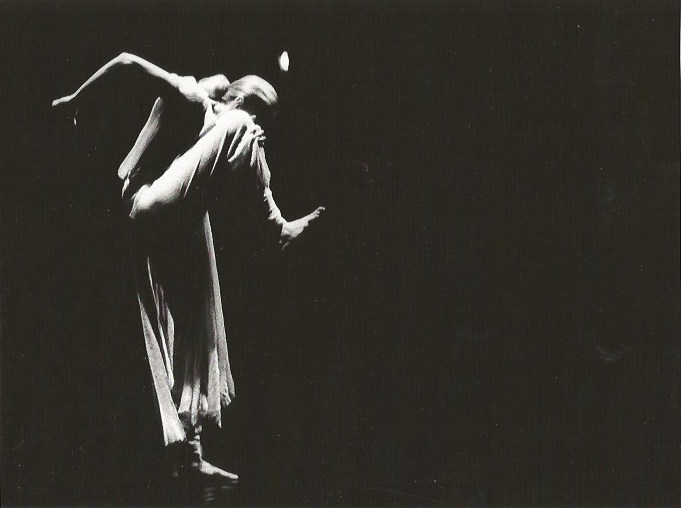

I distinguish dance with miniscule d and Dance with capital D. The dance with miniscule d is the common dancing I don’t despise at all, though. I remember when I was young we attended village firemen’s ball where we danced polka and waltz to brass band music.

It was a fabulous experience. The Dance with capital D is the one I try to associate with the name Duncan. Isadora Duncan was a genius who materialised the feeling of the turn of the 20th century, the necessity of the return and respect to nature. What’s even more ingenious, she didn’t allow to be filmed or photographed which would certainly look a bit funny now. I think that our task is to evaluate her legacy and make use of it at present. Dance is part of life, it’s not about standing on stage, performing and pretending. Dance with capital D is a way of life.

Do you miss dance? Are you still dancing today?

Do you miss dance? Are you still dancing today?No, not any more, I teach…. One day you find out that your body is not able to convey a message and then it’s time to stop. Fortunately, I decided in time, basically I retired from stage when I founded the conservatory. I was convinced that it made a lot of sense to the society at that time, we were all full of hope and willing to sacrifice many things to keep the society follow the same direction it had taken in the 1990’s. Back then I declared that Duncan Centre Conservatory would supply at least ten honest people every year (laughter).

Back to Dance with capital D… When I recall what I experienced in your classes, there’s one sentence on my mind: “Through the order comes the freedom.” For me, this statement symbolises all your teaching. Can you explain it to our readers?

I’ll explain it through a concrete example. When your body learns how to control itself by the rules which are organic, which nobody has invented by reason, you accept your personality and find a certain principle on which you want to exist, in other words you accept the order and then you can do anything. You don’t have to think of what you can do or cannot do, but you will never lie again, the body will resist. You don’t need any ‘policeman’ to tell you: you can do this, but you can’t do that.

I have one more word in mind – humbleness. Do you think it is fashionable today?

No, not any more. Today’s society is, in my opinion, too spoilt, focused on money, profit, success and power. The word ‘humbleness’ or ‘sacrifice’ is something that doesn’t belong to our world….and that’s very bad. We cannot generalise but there are many people who selflessly work for a good cause. But unfortunately, most people wrestle up for power and knock down those who stand in their way – horrible!

What do you think about contemporary dance creations?

What do you think about contemporary dance creations?I’ve tried hard to follow them, but I must say they don’t give me any pleasure. They don’t mean an experience for me. So, I go to see them quite rarely. I think that there’s something very wrong in the grant system. However, if I remember the time of my youth when we didn’t have any chance, when the system treaded us under its foot, mercilessly, the fact that the grant system exists now is a step forward. But the way committees operate is wrong. To think ahead what I can get some money for and base my creation on it, is absurd.

I also think that there are too many new productions and all organisations and companies care about is reaching audiences and have full houses. That’s simply perverse. There are and will be performances that are not supposed to be popular, that are just for a few connoisseurs. But it doesn’t mean they should disappear. There’s certain courage in it and pride of this art. Not to go with the flow and not to assume that current trends are the top, the smartest, the world’s best. For me, a good piece is enough, but it must be really good. Then I’d like to come to see it.

Do you follow contemporary dance criticism?

I don’t go to see performances, so I don’t have any reason to follow it. But I follow it more than the productions because I’m interested in the way people think about dance. I think dance criticism is frantically toothless. It misses deeper personal attitude, in my opinion. Nobody wants to take a wrong step, to upset or hurt someone because they are afraid of the consequences. Everything is too careful and leads to nothing. I think the truth emerges from a clash. Only when I have a proper argument with someone having a different opinion, there’s a chance that some conclusion might appear. Of course, I can’t state I’m impeccant and you are a fool – there would be no way out. We are afraid of the clash – you just need to go for it and struggle for the truth.

Eva Blažíčková (*1943) is the pupil of the Czech dancer, choreographer, and teacher Jarmila Jeřábková. She attended dance courses at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague and at Palluca Schule in Dresden. She is considered a continuator of so called Czech duncanism. In 1972 she took over Jarmila Jeřábková’s studio and successively formed three dance ensembles (Studio komorního tace I., II. and III.) where she was the director and choreographer. In 1992 she established Duncan Centre Conservatory and remained at its head until 2009. Last year she founded the Duncan Institute which is an umbrella institution for a dance studio and research rooms/archive. She has choreographed more than fifty pieces, e.g. Černé a bílé slzy (Black and White Tears, 1979), Zaříkání milého (1983-1986), Eufemias Mysterion (1986), Špalíček (2009), Kytice (2014). Besides her teaching activities in the Czech Republic and abroad, she is the author of Metodika a didaktika taneční výchovy (2004) and co-author of a publication Taneční a pohybová výchova (2011). She also committed herself to integrating dance and movement education into the Framework Educational Programme for Basic Education.

Eva Blažíčková (*1943) is the pupil of the Czech dancer, choreographer, and teacher Jarmila Jeřábková. She attended dance courses at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague and at Palluca Schule in Dresden. She is considered a continuator of so called Czech duncanism. In 1972 she took over Jarmila Jeřábková’s studio and successively formed three dance ensembles (Studio komorního tace I., II. and III.) where she was the director and choreographer. In 1992 she established Duncan Centre Conservatory and remained at its head until 2009. Last year she founded the Duncan Institute which is an umbrella institution for a dance studio and research rooms/archive. She has choreographed more than fifty pieces, e.g. Černé a bílé slzy (Black and White Tears, 1979), Zaříkání milého (1983-1986), Eufemias Mysterion (1986), Špalíček (2009), Kytice (2014). Besides her teaching activities in the Czech Republic and abroad, she is the author of Metodika a didaktika taneční výchovy (2004) and co-author of a publication Taneční a pohybová výchova (2011). She also committed herself to integrating dance and movement education into the Framework Educational Programme for Basic Education.

Josef Bartos

Thank you for your thoughts. One got stuck in my mind – that passion makes us different from AI. Just yesterday I read…I am a dance critic. I am a member of an endangered species