Be the frame

When the train leaves the station in Prague, I already start to imagine the bodies of my fellow critics from the three days spent together at a workshop and panel talk on dance writing at the Czech Dance Platform festival. As my train slowly embarks on its journey, I know Lena is still standing in the hall in Prague, waiting for the platform for her train to Budapest to be announced. And when she gets on the train, with her blue suitcase and silver backpack, we will be stretching out in a line across Europe. Lena towards the east, myself westbound to Berlin, where Emily is already – maybe getting ready to head out into the city with her brother, visiting from England. Daniela, Petra, Lucie, and Anna – as well as Tereza, Diana, Barbora, Viktorie, and Veronika are still in Prague. But soon members of this group will descend towards Paris, Ostrava, and Bratislava. The group is dissolving, spreading out into corners of Europe, like an ink stain, slowly eating itself into the map.

‘The review is subjective’, says Emily, and I want to cry with relief at having consensus in the room on this particular point. Not because I want consensus, normative formats, or ideological uniformity in the field of criticism or among critics, but because agreeing on this specific aspect makes it possible to discuss and explore a range of ways, modes, and formats of critical writing (and talking, drawing, and maybe even moving too). I met some other critic colleagues only a few days earlier where this was not the case. ‘But all criticism is journalism’, said my Norwegian (journalist) colleague, with a slightly puzzled expression on his face. ‘I am not a journalist’, I replied – not because I have anything against journalism or journalists, but because that is not my profession. I do not claim to be or even try to be objective, I don’t feel an obligation towards the performance, nor do I feel an obligation towards the reader – apart from giving or inviting them to read a piece that is worth the time it takes to read. My main obligation is then towards the texts I write, in finding a form that suits the material I have gathered from the performance I have experienced, but also the other material I have collected: From books I have read, places I have been, people I have met, other performances or exhibitions I have spent time with, the events, things, and beings that shape how I think. All of this material leaks into the performance, and thus also into the writing. Critical writing is, to me, both as a reader and writer, an invitation to think alongside, against, and with the performances. It can be service-minded towards the performance, but – as Irit Rogoff once asked: ‘Can looking away be understood not necessarily as an act of resistance to, but rather as an alternative form of, taking part in culture?’ That having an awareness of or paying attention to other things, people, or other beings than those on stage, can also be a part of or even a focus of a piece of critical writing. Diana Damian Martin calls critical writing a ‘choreography of attention’:

As the lights dim, I become part of the fabric of this performance. I forget to take notes; perhaps occasionally, I am reminded of something else, creeping in from the edges of my memory, and this gives my encounter, in that moment, particular significance. This choreography of attention unfolds throughout my encounter, and later, as my eyelids start feeling heavy, as I rummage through my notes, as references and histories start pouring in, I begin to hack at this piece of criticism. Somewhere in that process, the performance starts to drift away; I move it back, and we dance together.

*

The journey from Prague to Berlin is very literally turning out to be an example of slow travel. Thirty-five minutes into the journey, at Kralupy station, the first delay occurs. Soon after, the delay increases to twenty minutes. In my experience, one delay will most likely lead to further delays, as the already-delayed-train will not be prioritised over the trains running on schedule. Better to have one very delayed train, than several with slight delays, seems to be the working motto of the railway companies. My empirical data collection in this department expands, as a new delay is added only minutes after the initial is announced. After two hours on the train, we are forty-one minutes behind schedule. But the station announcements seem to be pre-recorded, as the train approaches a new station and the voice on the intercom states: ‘The train has an estimated arrival of 10.20’, while my phone clearly shows the time to be 10.39. It appears that we will somehow arrive in the past.

*

‘The blog was intended as a sort of wellness centre for my brain’, says Barbora. It’s the first day of the workshop, we are only ten minutes into the first session and already my brain is being picked, tickled and massaged by the ideas, wordings, and knowledge of the other critics in the room. Perhaps criticism for us critics almost has to be a wellness centre for our brains, as the payment is usually low (or non-existent) and the working hours unconventional? The thought of navigating towards or around criticism as a wellness centre for the brain is certainly inviting, mesmeric somehow. It is also perhaps this aspect that draws me towards the term ‘critical practice’. The term implies that being a critic – the one carrying out the critical practice – is something that is done, something performed. Critic Theron Schmidt’s article How we talk about the work is the work (2018) is a piece of writing I keep coming back to in my own work. It’s something about putting the work of writing or talking on display, how the writer is included in the conversation about, with, or on the performance, which I find vital. This notion of being neutral or objective tends to hide the critical process of choosing. How everything is a choice: what you write about, how, with which words, in which context, in which tradition you see it, how you value it, etc. None of these are neutral; deeming a performance as ‘good’ usually happens within a very specific context, which shows off the critic’s references and values, just as much as the art field. Critical writing that manages to stage a conversation between what happened on stage, what happened in the audience (both the writer and their co-audience), as well as references, ways of understanding dance, and personal experiences from other parts of the writer’s life, are the types of texts I keep returning to or seek out.

*

‘The train is now thirty-nine minutes delayed,’ announces a voice in German on the intercom – followed by an English version where the train is only thirty-four minutes behind schedule. Five full minutes are somehow lost in the translation. And the English appears to be more optimistic than the German – but in the end, the latter will turn out to be right.

*

Through the seminar we have shared the experiences, joys, and frustrations from our critical practice. Meeting in a language that for most of us is not our mother tongue, our second or even third language, also means the discussions and sharing is a continual process of translation. Working within very different contexts and institutions, the boundaries and possibilities in our practices differ. These translations are not only a question of language – between Norwegian and English in my case – but also between experiences and context. How do I translate the relation and process I have with my editors, the economical patchwork that also is my practice, or the work that I do which is not writing reviews, yet that I still think of as part of my critical practice? We get lost in these translations on some points, but we also transgress. We stretch toward one another, we reach out and meet each other halfway there. ‘For me, the critic is a travel writer, always going far from home, invited as a guest into someone else’s place,’ writes architect and critic Jane Rendell:

To enter the territory of another necessitates movement out of one’s own – it involves trust on both parts. To engage with something imagined by another is also to journey, from what is already known towards what is yet unknown. To encounter another requires a willingness to connect, but also to let go, to take risks. Some critics travel like tourists, crossing vast territories but remaining unchanged. Others are constantly pulled out of the familiar towards the strange, impelled by a desire for transformation – a total immersion on the other – in order to return anew to the self.

I am not sure to what extent I travel as a tourist or whether I am pulled towards transformation, I reckon it is a combination. To always travel – within the performing arts – with a desire to be totally immersed by others, seems difficult to me. As Jennifer Doyle states: ‘Critics have limits’. I sure have mine, and I try to be as up-front about them as I can. But as Doyle goes on to write; critical practice is also a way to find those limits, and writing is a way to negotiate them, discuss them, and maybe even to go beyond or transcend them. In the meeting with other practices, my view of what criticism is or can be (or if one should follow Rogoff again, and use the term ‘criticality’ instead of ‘criticism’) is changing. Perhaps not fundamentally, but rather it is adjusting and stretching to include more. Becoming more generous and inclusive.

*

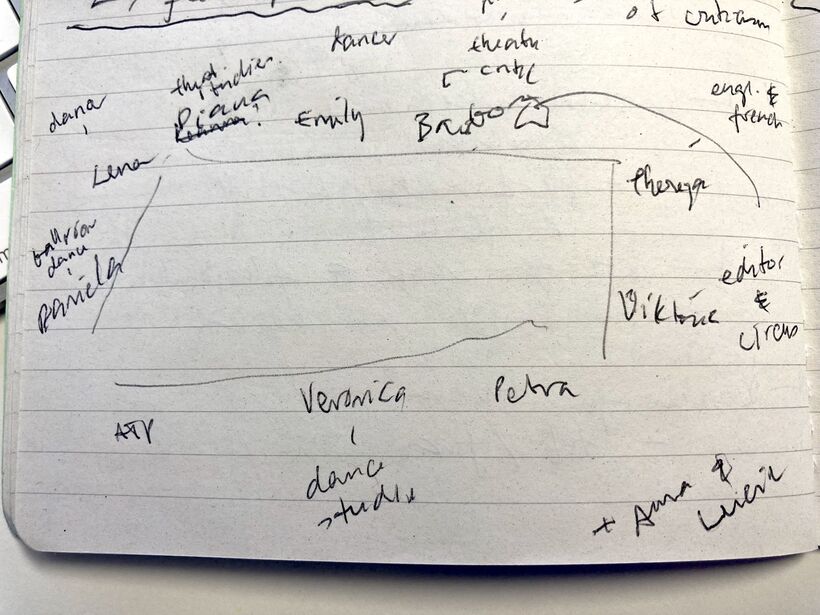

Time passes. Days turn into two weeks, and I have travelled further north to Oslo, where I live. I am finishing an article on affect as part of the Ph.D. I am working on, where I write about affect in the way Sara Ahmed defines it; as something sticky – that affect is what sticks. And as I think back to those days in Prague some things stick more than others. I made a simple drawing of the table in the workshop room on the first day, scribbling down the names of the others and placing them around this table (which basically is a square, my drawing techniques are not particularly advanced), with notes on what they do or their background. Viktorie has the notes ‘editor & circus’ attached to her name, Veronika has ‘dance studies’, and Daniela ‘ballroom dance’. This drawing sticks, and as I focus on it – in my mind – the bodies and faces of the people around the table, and elsewhere in the room, come to life. I see Diana leaning back on her chair, Tereza’s hand gesticulating – and snippets from the conversations keep popping up as I walk the streets of Berlin. As I finish my academic article, they sneak into my journey back to Oslo and now, as I try to find a way to finish this piece of writing, the bodies of the others are gathered in my imagination. It is much the same method of writing as when I write about or alongside performances; I try to connect with what sticks and write them back into their original shape, or into new shapes. The American writer Dodie Bellamy wrote in her essay Barf manifesto about the reason she stopped writing reviews: ‘the form was killing me, the suppression of the self, the tidiness, the pretence of objectivity (…) Perception is about framing; when it comes to doling out opinions, I am the frame.’ I have used these lines from Bellamy as a means to end a text before. I find it inspiring to imagine oneself as the frame of one’s critical writing – in whatever format that may be. It could be a review – short or long, with or without images or drawings – letters or conversations, creative writing, emojis, essays or something else entirely. Be the frame. Be part of deciding what dance writing is and can be.

References and further reading:

Ahmed, S. (2010). “Happy objects”, in The affect theory reader. Duke University Press.

Bellamy, D. (2015). When the Sick Rule the World. Semiotext(e).

Damian Martin, D. (2016) “Criticism as a Political Event”, in Radosavljevic, D. (ed) Theatre Criticism: Changing Landscapes. Bloomsbury.

Damian Martin, D. (2019). “Hopeful Acts in Troubled Times: Thinking as interruption and the poetics of nonconforming criticism”, in Performance Philosophy, vol 5, no 1.

Doyle, J. (2013). Hold It Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art. Duke University Press.

Hilevaara, K. & Orley, E. (Eds) (2018). The Creative Critic: Writing as/about Practice. Routledge.

Pettersen, A. T & Sandvik, M. V. (Eds) (2018). Criticism for the absent reader. Uten tittel forlag.

Pettersen, A. T. (2020). “Young Critical Practices: Ways of Thinking in and with the Arts”, in Critical Stages, issue no. 22.

Rendell, J. (2010). Site-Writing:The Architecture of Art Criticism. I.B. Tauris & Co.

Rogoff, I. (2005). “Looking away: Participation in visual culture”, in Butt, G. (ed), After Criticism: New responses to art and performance, Blackwell Publishing.

Rogoff, I. (2008). “What is a theorist?”, in Elkins, J. & Newman, M. (Eds). The state of art criticism. Routledge.

Schmidt, T. (2018). “How we talk about the work is the work”, in Performance Research, vol. 23, issue 2.

Editor's note: This text was written as part of the Dance Criticism in a European Context project. The project was supported by the European Union and the Ministry of Culture through the National Recovery Plan.

.jpg)

.jpg)