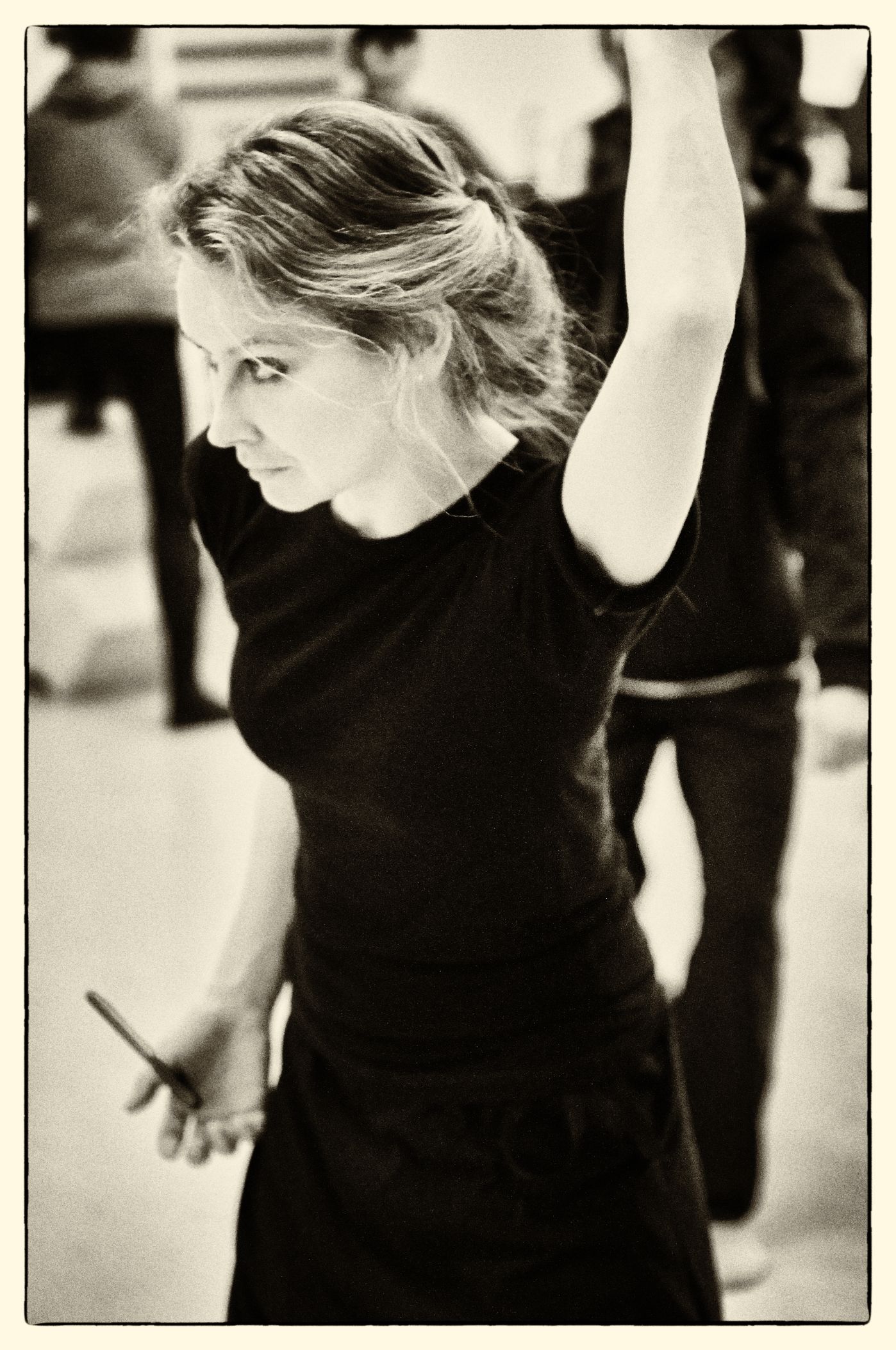

The premiere of your Rite of Spring – a touchstone for all choreographers - is coming soon. Do you have any favourite version of this piece?

I have seen many versions, some I liked more, some less…. it is the libretto that matters for me. I adjusted a lot of things in the libretto, including the music as I make use of other scores than just The Rite of Spring. The first part, for example, is set to Stravinsky’s Apollo Musagète. Typically for me, the piece consists of two levels. I like the alienation effect, ruining the illusion of theatricality. The first part takes place in the time and space of Stravinsky - the composer. When I was reading through The Rite, I was fascinated by the frequent use of the word ‘sacrifice’. Also the artist has to make sacrifices – to his Muse, a woman. Will the composer be able to create a piece, hardly understandable for anyone else but him, at the peak of his career? To sacrifice his repute and well-being, and maybe also health, only for the truth of music? The composer agrees and the society, very supportive so far, becomes horrified and averse. But the situation is slowly changing and The Rite of Spring begins. The ever-classy society turns into a bunch of pagans and shows the composer what he actually created. But the composer can intervene and demonstrate what will happen if they profane the life on Earth. It made me almost sick at times how much repulsion, intensified by the alienation, the sacrifice provokes. In my version, the sacrifice is embodied by a female dancer who wants to leave but the other dancers don’t let her go – they are so absorbed into the play and they need her. But I did not wish for a tragic ending so it all culminates in an apotheosis of love. You decided for a positive ending because of the audience, not to make them too depressed?

Not really, I needed it myself. I’m optimistic and idealistic. And I believe that human sacrifice might contribute to something good, to social revelation. We can only change through personal sacrifices. Where did you seek inspiration for your conception? Inner struggle is a frequent leitmotif in your works.

The theme of an individual versus society is very important to me, as well as a storyline. I also often use the motif of alienation – which stems from my life approach. In life and in work, I incline more to Brecht than to Stanislavsky. I don’t think we should perceive ourselves as ‘us’ or ‘I’ but rather as ‘he’, in the third person. And then the observation from outside and the self-evaluation becomes possible. I don’t accept Stanislavsky’s theory of plunging deep into the role and asking: ‘How would I experience this?’ On the contrary, I’m interested in how the hero experiences the part. This depersonalization is crucial for theatre and for life. Petr Zelenka works with a similar idea in his film The Brothers Karamazov. That’s why I try to somehow frame my pieces – to make the viewer realise: ‘Ok, but this is not the story of Romeo and Juliet that took place many centuries ago. There are Romeos and Juliets among us nowadays’. I was digging into the score for ages and couldn’t find the key. What really helped me was Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music which is now like my Bible. It is a collection of the composer’s lectures for the Music Theory students at Harvard which are very philosophical and soulful and they penetrate many fields of human experience.

The premiere is very close, how do you feel?

The theme of an individual versus society is very important to me, as well as a storyline. I also often use the motif of alienation – which stems from my life approach. In life and in work, I incline more to Brecht than to Stanislavsky. I don’t think we should perceive ourselves as ‘us’ or ‘I’ but rather as ‘he’, in the third person. And then the observation from outside and the self-evaluation becomes possible. I don’t accept Stanislavsky’s theory of plunging deep into the role and asking: ‘How would I experience this?’ On the contrary, I’m interested in how the hero experiences the part. This depersonalization is crucial for theatre and for life. Petr Zelenka works with a similar idea in his film The Brothers Karamazov. That’s why I try to somehow frame my pieces – to make the viewer realise: ‘Ok, but this is not the story of Romeo and Juliet that took place many centuries ago. There are Romeos and Juliets among us nowadays’. I was digging into the score for ages and couldn’t find the key. What really helped me was Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music which is now like my Bible. It is a collection of the composer’s lectures for the Music Theory students at Harvard which are very philosophical and soulful and they penetrate many fields of human experience.

The premiere is very close, how do you feel?Besides dance there are several things that I look forward to very much but they make me worried at the same time. It concerns the visual side in particular – the scenography was designed by my brother Richard. In the centre of the scene there is a shot-into-pieces piano which symbolizes the torn-up music of Stravinsky. My brother was incredibly precise about the golden sections – this is homage to Stravinsky who worked in closed forms and advocated the limitations of an artist. I’m also afraid of the moments when the dancers manipulate with scattered-around corn – it looks very impressive but it’s also slippery and sometimes painful. And I rather don’t imagine what the technical staff think when they have to clean the stage after performance… (laughter). When you became the Director of the ballet company in Liberec, you defined some goals you wanted to achieve – for example to level the technical skills of the dancers. You have been with the company for five years – have you accomplished your goals?

I have, partially, but in reality I had to give in at many points. I wanted to work with people who would have adapted to my style and be OK with it – and in some cases I really made it. It was not possible to renew the company significantly, as there were permanent contracts. Liberec is probably the last place where such a system has long existed – I managed to change it two years ago but some contracts are still valid. And at the same time the company is so small that we only work with one cast. However disciplined you are, the absence of competition always plays a part. I feel that every time I choreograph for a bigger company where dancers fight for standing in the first line. In Liberec, everybody’s role is secure during the season. There’s no possibility of comparison with other dancers, either, which means the company members cannot develop their roles in this way. On the other hand, I can pay my attention to everyone. I don’t take it as a negative or positive thing, just as a fact I have to cope with.

Translation: Tereza Cigánková