Interview with Helena Kazárová, a teacher, director and choreographer: “I wanted to be a dancer.”

We have known each other for many years. We met for the first time as students in the Ledebour Palace, which then housed the Dance department of the Music Academy of Performing Arts, and later we were both members of the Czechoslovak State Song and Dance Ensemble. Though our careers took us in different directions, we stayed in touch. For some time now, we have been both back at our former alma mater, dance being one of many things we talk about. Helena has encouraged me to try a Baroque étude, dance pavane, minuet and bourrée, and thanks to her, I have fallen for the beauty of antique brooches that we sometimes admire together in a small antiquity shop near HAMU (Music Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts), located in the Lichtenstein Palace. That is where we met earlier this September to look back at the past years, as time is flying too fast, and Helena’s life anniversary is fast approaching…

I didn’t want to sit in a library

You were admitted to the Dance Department of HAMU after your final exam at a grammar school. How did you get to dancing? What prompted you to study dance theory?

I simply wanted to be a dancer. But my parents saw such a career very sceptically, my father (prof. Ing. Dr. Jaroslav Hájek, DrSc.) was devoted to mathematical statistics, he was a professor at Charles University. He thought that a good dancer was the one who danced a swan in a big theatre. He said if I failed, I could end up dancing in a bar. And he couldn’t let this happen. At that time, he was already seriously ill, so when I was meant to enrol in a conservatoire, I simply couldn’t go against his wish. My parents told me: “You’re good at languages, so you’ll go to a grammar school.” My mum wanted me to study law later (my father died when I was fourteen), but I revolted. I said a clear “no” and set my mind on HAMU. I did my best to get there. But attention, please, I wanted to study dance pedagogy, and so I did.

Was it Prof Božena Brodská, who drew you to dance theory?

No, I can’t say that. For one semester I studied dance pedagogy under Olga Pásková and Věra Ždichyncová. I enjoyed it very much, but I also got married and expected a baby. It was more likely for me to finish dance theory studies. So, in the summer semester, I started to study dance theory under doc Brodská and Vladimír Vašut.

But your dream eventually came true. You danced with the Czechoslovak State Song and Dance Ensemble for two years. Did you feel it necessary to try dancing on stage?

Definitely. I longed to be a dancer. I had good proportions, too, and slim legs. Before studying at HAMU, I attended the Motorlet ballet studio, but only once a week which was not enough. I also tried dancing on pointe there – I put my pointe shoes on, stepped on them as if I had always worn them, which also my teacher commented on, with surprise. For me, dance theory was not without interest, I just didn’t see myself, aged 24, sitting in library and doing research for the Theatre Institute, as prof Vašut suggested. I told myself that if I was meant to write about dance, I had to try it (even as a back-row dancer). Otherwise I wouldn’t have known what stage dance was about.

Later, you started teaching at the Dance Conservatoire of the City of Prague. To get a job in the field wasn’t easy, even back then.

First, I started teaching at HAMU in 1989. Prof Brodská called me and said the department was looking for a academic assistant. I went for it and when my colleague Ivanka Kloubková moved abroad, I took over her subjects and many more. It was a big challenge. Suddenly, I was giving lectures to my peers and to students just a little older than me. I taught subjects such as classical dance for pantomime, dance aesthetics (a new subject), dramaturgy and others including dance history. In 1990, I signed a contract for an academic assistant. However, it was a turbulent time, there were strikes and change of department heads.

Back then, Eva Melicharová was looking for a full-time dance history teacher. And because the situation at the Academy was uncertain, in 1991 I signed a full-time contract with the conservatoire. The job was incredibly interesting, to see the day-to-day progress of young dance students was unique.

Working freely with music is beautiful

At HAMU, you studied dance theory, which later transformed into dance science. You participated in its establishment and development. What do you consider to be your biggest contribution to this domain?

Since 1990’s, I’ve tried to promote openness to the world, which was not rooted in the field of dance history. There were foreign magazines such as Dancing Times, videos, I remember the screening of Balanchine’s ballets at Jan Hartman’s place before 1989, it was full! But it wasn’t enough. Opening to the world was vital for me. I tried to make contacts with dance history societies that also published specialised journals. I’m a member of the European Association for Dance History. The access to foreign literature is essential for dance science. Today’s students are not always able to work properly with searching tools such as Google, and as a representative of the older generation, I must point out to them that they have incredible possibilities of reaching data. They can access digitalised sources we had to rewrite once… In this respect, it’s easier for them now, however, it’s much harder to deal with the information overload.

Back to your own contribution… You have published two books devoted to Baroque dance and Baroque stage forms. What fascinates you about this period? I know it’s close to your heart.

I’m kind of a researcher. Since childhood, I’ve loved to play princess games… Prof Brodská focused mainly on dates of premieres and biographical facts, but she wasn’t’ much interested in visualisation, she didn’t work with iconography that could not be easily accessed at that time. First, I concentrated on iconography which awakened my curiosity about how the period dances had looked like and how I was supposed to imagine them if I wanted to write and talk about the Baroque. This led me to international courses where I saw for the first time how Baroque dances had been performed to period music. I got interested in Beauchamp-Feuillet notation. Prof Brodská opened that door for me, as she owned books on notation systems.

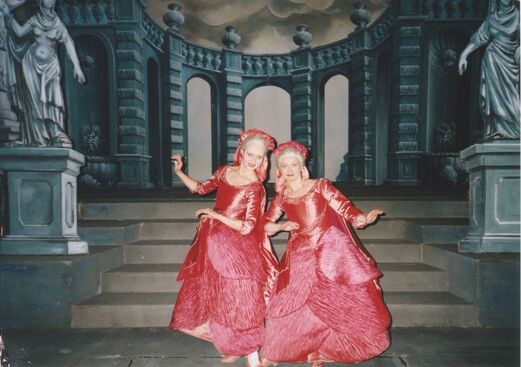

You also wanted to share your knowledge, and so you founded Hartig Ensemble, with which you have staged numerous productions. If I remember it right, one of the biggest challenges for you was the 1999 collaboration on the Baroque opera Castor and Pollux in the Estate Theatre.

It was my first professional experience with such a complex movement material. I wasn’t inexperienced, I regularly travelled abroad and attended conferences on dance history, and I’d seen commented demonstrations of Baroque dances. At the Academy, I enjoyed teaching dance history through examples, therefore I created a sort of class laboratory with my students where we attempted to reconstruct Baroque dances based on the information we had. They were my first “laboratory rats”. I took them to a conference in London where we performed the reconstructions of two sarabandes. This pushed me to set up a student ensemble. We were given the opportunity to perform at Týn school with musicians specialising in historical interpretation of Baroque music. There I met Jana Semerádová, Marek Štryncl, Václav Luks and others whom I saw again during the preparations of Castor and Pollux, when assisting the choreographer Marc Leclercque.

Was it an impulse for you to start reviving Baroque pieces? You began to take part in staging period pieces, as a director and choreographer. It was the next step forward.

It wasn’t the first impulse. Before Castor and Pollux, I attempted to revive Baroque dances according to Beauchamp-Feuillet notation. In 2000, I took part in the staging of Jan Dismas Zelenka’s Pod olivou míru a palmou ctnosti (Sub Olea Pacis et Palma Virtutis) in the Vladislav Hall. It was supervised by the conductor Marek Štryncl and played by an extended Musica Florea orchestra. I invited Marc Leclercq to be the choreographer and director. He named me his assistant, for both the choreography and direction, which was demanding.

From the summer courses of ancient music in Valtice (where Prof Brodská had sent me) I knew Robert Hugo, who began to do Baroque opera with his musicians and invited me for movement collaboration and choreography. We have staged a couple of successful productions together. We presented the Baroque opera Praga Nascente da Libussa e Primislao at the Prague Spring Festival, where I choreographed my first own piece to Fisher’s suite (for more information, go to https://youtu.be/y94SdIlmjbQ).)

Choose your words wisely

You also write reviews. Lately, the purpose and importance of dance criticism has been argued. What is your view?

Since my studies at the Academy, I’ve felt I owed a great deal to Czech professional dance. Generally, not many people write about it. Dance criticism is not a piece of cake and at times, I felt a burden on my shoulders. I’ve been writing a lot, now I’m trying to finish my bibliography, on the occasion of my life anniversary, and it’s rather difficult. I’ve been writing about amateur dance, dance competitions, professional dance, premieres, portraits – but eventually, you need to choose one thing. When I was in close contact with Vladimír Vašut who helped me immensely with my first attempts at critical writing (by being critical towards my texts), I felt bound to write about professional dance art. A dance critic should have deep knowledge of dance, be able to watch closely and with insight. Now, I observe the discourse from distance, but I don’t take a stand. There are many opinions on what art and dance criticism should be, also abroad. It’s just necessary to look outside the box, to see what’s going on in the world. And there are things we shouldn’t copy. For example, American dance criticism assesses everything based on gender equality. Choreographers are openly attacked for being discriminative. Criticism is becoming the ethical and moral police. That’s not right, I suppose…I’ve also heard an opinion that criticism should be a literary and poetic accompaniment to what happens on stage. It’s also possible and some authors do it.

I’ve adopted a motto by the Israeli historian and critic Gior Manora. He claimed that when he wrote critically, he asked himself three questions: “Is it kind?”, “Is it true?” and “Is it necessary?”. This is very wise. Professional critics must write, whether they wants or not. but there needs to be a certain level of sophistication. They must choose their words wisely, because words can be weapons and a reviewer should not fight. A reviewer should put his impressions, which are subjective of course, into certain contexts.

Criticism is considered to be a half-artistic and half-specialized literary genre. It’s Prof Vašut’s legacy and I respect that. To use a beautiful language, be able to tell your truth (as seen through one’s own experience), not to aim arrows at creators and performers to make them feel awful. A reviewer is also a promoter, he promotes a piece. A century ago, Dhagilev knew negative criticism made good promotion.

Prof. Mgr. Helena Kazárová, Ph.D., a dancer, choreographer, dance historian and theorist, publicist and teacher (born on 29 September 1959). In 1979-1983 she studied at the Music Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. From 1983 to 1985, she was a member of the dance section of the Czechoslovak State Song and Dance Ensemble. In the following years she worked as the regional methodologist of the dance department of the City of Prague Cultural Centre of. In 1989, she became an academic assistant at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. Concurrently, she worked at the Dance Department as an external teacher. Becoming a lecturer at the Department in 1998, she has focused on the challenging teaching practice ever since.

In 1998-1999 she was the chief-editor of the specialised journal Taneční listy. She applied her teaching skills in the domain of dance theory (including dance history) during her collaboration with the 1st Private Dance Conservatoire of Ivo Váňa-Psota in Prague (1998-2004). In 2001 she defended her habilitation thesis at the Academy of Performing Arts and was appointed ‘docent’. She completed her postgraduate studies in 2004. Currently, she is a professor (named 2011) at the Dance Department of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague.

Since 1997, she has been the head of the Hartig Ensemble – Dances and Ballets of Three Centuries which she founded and for which she has created a broad repertoire of dances, reconstructed according to Beauchamp-Feuillet notation and other sources.

Source: https://www.fdb.cz/lidi-zivotopis-biografie/441146-helena-kazarova.htm https://www.hartigensemble.cz/index.php/o-nas/umelecke-vedeni-souboru