Today we are celebrating the birthday of one of our prominent dancers and classical dance teachers, Jaroslav Slavický. The former first soloist of the National Theatre Ballet in Prague and long-term director of the Dance Conservatory of the City of Prague looks back at his eventful life with the muse Terpsichore and he reveals what he misses in dance and what issues he would like to be discussed more. But first of all – Happy Birthday!

Your birthday interview would not be complete without a brief recapitulation of your dance journey. You were born in Poděbrady, your father was a teacher and a musician, he founded several ensembles, a music school, he was a member of a spa orchestra…one would expect you should have followed in his footsteps.

Originally, it seemed that I would, as a boy I dreamed of a singing career. At home we had a bookcase full of specialised and popular music publications, I loved Sto operních libret (One Hundred Opera Librettos). I read the contents, the passages about composers and casts of various roles. I wondered whether I should become a lyrical or heroic tenor. In Poděbrady I attended a music school, I sang in a choir and played the piano. At 10, my desire to prepare for an opera singer career led me to our Prof. Plojharová. Of course, she told me it was too early to start singing opera. However, I was also a keen mover and danced to songs I heard on the radio and it seemed I was talented. And so I started to attend rhythmic gymnastics classes.

Were you the only boy in the classes?

in Poděbrady I was the only boy who did rhythmic gymnastics, but no one laughed at me and made it bitter for me. I also performed a lot. Poděbrady is a spa town, so we danced for spa guests, and I got really interested in the world of dance and performing. I remember we had dance classes on Thursday. Thursday was a Day D for me and I looked forward to it for the rest of the week. Mrs Soňa Macháčková travelled to Poděbrady every week to teach dance. It was an amazing woman who taught us classical dance technique and a bit of modern dance. We also did some basic steps of character and folk dance. She created choreographies, sewed costumes and took care of us. It was all very inspiring and creative. And later, when we moved to Prague, shortly after my father had been released from prison (he was imprisoned during the period of political trials and released after the first amnesty for political prisoners in 1960; editor’s note) and I started to attend the preparatory courses at the National Theatre, I kept attending her classes, too.

Were you satisfied in the National Theatre preparatory course?

Compared to Poděbrady, it was a completely new world. We appeared in some productions of the National Theatre and it was marvellous. We did pages in Rusalka or in the ballet Othello. In Rusalka, I watched Mr Haken and Mrs Šubrtová from the wings, and Vlasta Šilhanová, Naďa Blažíčková, Jaromír Petřík or Viktor Malcev dancing in Othello. Theatre industry fascinated me, and it drew me closer to dance. My transition to the conservatory was very smooth as I didn’t even think of doing anything else.

Was the schooling too different at that time?

I don’t remember exactly. I enrolled in the school in 1963, and entered a five-year programme with practical subjects similar to what we know today. Of course, classical dance and folk dance were especially accentuated at that time, and the instruction was at a very high level. Folk dance was taught by Míla Urbanová and František Bonuš, passionate folklorists, who were cruising the coutry and collecting dances and songs. They hooked us completely. We were quite old, we went the conservatory after elementary school, and learning classical dance basics was terribly boring. We wanted to dance and in folk dance classes we really could.

Which of the teachers do you like to remember?

Our ballet teacher was Dr Tymichová, a very sophisticated lady who had danced in Paris for a long time. She gave us strong foundations. In the third year, we got Prof Karel Lukšík, the first soloist of the National Theatre Ballet. There were seven boys in our class, we had an “all-male” group, so the lessons were dynamic and full of energy. Věra Urbánková taught so called modern dance, which was great. The conservatories of the Eastern block didn’t usually provide modern dance classes, except for Palucca Hochschule in Dresden having tradition in expressive dance. Věra Urbánková had studied in London and she’d brought with her the basics of Martha Graham technique and other flourishing dance styles. We didn’t learn character dances and we started with ‘partnering’ in the fifth year.

Foreign experience

Foreign experience

After passing your school-leaving exam you were awarded a scholarship in the then USSR. It must have been a big change to study at such a prestigious academy. Did you feel ready and well-prepared?

I won the scholarship along with my classmate Michaela Vítková. First, we wanted to go to Moscow but eventually we arranged our Leningrad stay and spent one year at the Vaganova Academy. If I felt ready? Well, the teachers at the Prague conservatory were prominent dance personalities of their time. There was no unified system, everybody related on their own sense of teaching, but it wasn’t at all bad, we came to the USSR with good foundations. In Leningrad, they put me into a master class for students who had finished schools across the United Republics. The best students were sent there to improve their skills. They had passed an eight-year programme, we had only five years, so there was some difference, but we were motivated enough to work hard.

What was the atmosphere and people like at the Academy?

Thy Academy was associated with legendary dancers and teachers. In the corridors, I used to meet dancers we’d learned about in the history of dance. Fantastic! For me, it was great experience, the students had perfect dispositions, talent and commitment. The teachers were wonderful too, both artistically and personally, for example Alexander I. Puškin or Boris Bregvadze who later worked with the National Theatre Ballet as a ballet master and stage manager. At that time, he had just finished his stellar career at Kirov and he was like a dream. Even if just marking, he showed incredible coordination and elegance. Partnering was taught by the great Nikolai Serebrennikov. In January, when we returned home for holiday, I negotiated one more year of scholarship at the ministry. I bought a flight ticket for 28 August and on 21 August, Russians invaded our country. I decided to stay in Czechoslovakia and join the National Theatre Ballet.

But you didn’t stay with the National Theatre Ballet for long, in 1969 you left for France. What about the border closures?

I was lucky. We performed with the National Theatre Ballet at the festival in Bregenz and we got back home on 21 August, late evening. Prague was bustling with demonstrations and tanks and I said to myself: “I’m not going to stay here, I must leave.” I went to Pragokoncert and they found me a place in the Strasbourg ballet company which was looking for a premiere danseur. In addition, two of my classmates were dancing there. I informed the National Theatre that I was not going to join the company. Luckily, I hadn’t signed my contract for the upcoming season yet. The director Jiří Němeček got angry, naturally. I couldn’t step into the National Theatre studio, so I missed the opportunity to train before everything was set up for my departure. I visited Pavel Šmok’s studio in Střešovice, the home of Prague Ballet. I had attended the company’s shows since its foundation in 1964. Pavel Šmok told me they had no ballet master, and that I could take the job. He offered me a contract, as the company was heading for Germany, but I had already signed a contract in Strasbourg. I departed on the evening of 10 October. We arrived to Cheb and at midnight they closed the borders. All passengers on the train were forced to go back, except for people holding service passports – it was one music band and I with a passport from Pragokoncert.

You danced in Théâtre Municipal in Strasbourg for one year. What kind of work discipline did you experience there?

I was given many opportunities, the company was international, having about thirty members. We performed in blocks, which means that one production was staged, it ran for some time, and then it was withdrawn, and the company rehearsed another one. I experienced French ballet technique I hadn’t known before. On the other hand, the director Jean Garcia asked me to give some trainings because they were interested in the Russian technique. At the end of the season, Pavel Šmok and Prague Ballet gave some guest performances in Strasbourg and Šmok offered me a contract in Basel, where he was to assume the position of the local ballet’s director.

Did you enjoy the two seasons with Šmok?

The engagement was wonderful. I met my future wife Kateřina there. She’d come with Pavel Šmok from Brno after the world premiere of Glagolitic Mass that Šmok had staged back in Brno and where she had danced the principal role with Jan Šprlák-Puk. The work on productions there we prepared with Pavel Šmok, and later with Luboš Ogoun, was also interesting. Small-scale creations were new to me. I remember the world premiere of Sinfonietta that Šmok created four years before Jiří Kylián, we did Burghauser’s Servant of Two Masters, two original ballets, Brain Ticket – a parody of Swan Lake – and The Drunken Ship about the life of Arthur Rimbaud. The work in the company was extremely creative.

Did he give space to his dancers and their ideas?

He had some vision, especially dramaturgical, and choreographic, of course, but sometimes he let the dancers try something themselves, sometimes he fixed their ideas, sometimes he developed them. He could step back if he saw his vision didn’t work. He wasn’t an authoritative choreographer. But under Pavel Šmok, we also performed in blocks. We rehearsed a piece, performed it for some time and then we had a derniere. After some time, I missed long-term work on a piece and finally my wife and I re-joined the National Theatre Ballet and stayed with the company until the end of our active careers.

Good genes and journey towards dance pedagogy

Have you always felt a calling to be a dance teacher?

I’ve always liked to teach because it allows you to look at dance from the other side. You execute a step and you must understand its principles, why something works or not. Back in Leningrad I enrolled in methodology courses led by two teachers, Shiripina and Kostrovicka, who opened two-year courses for the Leningrad Academy graduates so that they could extend their teaching education. I started to focus on dance teaching methods and how movement was created. Probably I have some genes for it, both my parents were teachers, they met at the Teachers’ Institute, where my mother was a student and my father was a lecturer. When I came back from Leningrad, I sometimes led optional trainings at the National Theatre. Until then, nobody had spent such a long time in Russia, people had usually stayed for two months as trainees at the theatre, but we were the first dancers who had studied right at the Academy.

Having returned from abroad, you began to teach at the conservatory. How did it happen?

By chance, again. At that time, my former teacher Karel Lukšík along with Astrid Štúrová were leaving for a three-month teaching internship in Leningrad and he asked me to take over his class. And so I had “my” new students such as Lubomír Kafka, Jan Kadlec, Vladimír Nečas, Martin Barotek and other future excellent dancers. Prof Lukšík prolonged his stay to six months and I went on teaching his class. The following year, Astrid Štúrová, the head of the dance department, offered me to teach dance practice, that is repertory. It came by the way, I didn’t push it.

However, you studied dance pedagogy at HAMU much later. Why?

It was a kind of “command”. On the New Year’s Eve 1982 we danced Giselle. I danced Albert and when leaving the theatre after the performance, I met Prof Božena Brodská waiting for me at the reception. She told me: “You’re studying at our school from September.” She’d arranged it with Mr Němeček so I started to study at the Academy of Performing Arts at the age of 35. The programme lasted for four years and I was allowed to merge the third and fourth year. Looking back, I see it was foresightful because if you want to assume the function of a director, you must have a master degree in the field of pedagogy. At that time I didn’t feel the need to study pedagogy. Along with theory, you also need practice and individual approach to students. What works with one, does not necessarily work with another, we should still remember that.

Are today’s students different from the previous generations?

I think today there’s not enough humbleness. People want everything, and they want it quickly, they need instant results. They think they have the right to do anything but forget what really matters - quality, in work and in studies. How much effort and time are you able and willing to invest to achieve a good result? It’s all in your head, it’s necessary to think about things, be prepared to work hard in class, not just wait and know nothing…… I don’t like when people say dancers just do some steps. Of course, physical performance is fundamental, but the work is very sophisticated. You can’t learn everything at school, that’s impossible, a school can give you good foundations for further development. What I find most important is teaching students how to approach the job professionally, how to be responsible and aware of what the job takes. You must be committed to your job all the time, not only when you are in mood for it. These are the essentials of professional work, it can’t be otherwise. Some technical elements – pirouettes, jumps etc. – can be refined but the approach is crucial.

Right place right time

Do you follow the careers of your former students?

I do. And I’m happiest when I see they’ve got very far and haven’t stayed at the same level they had at school, though they were good students. When young dancers leave school aged 18 or 19, they are officially adults, but they are still maturing, both physically and mentally. I’ve experience this in Bohemia Ballet where people can change immensely within one year and they start to perceive the whole profession very differently.

Do you think the immaturity you mention is the reason, why so many young dancers don’t make it to the Czech National Ballet, that the company prefers overall maturity of its dancers?

The issue of problems with graduates has already emerged this year, it was discussed at the meeting of the Czech Dance Association, where Lenka Dřímalová opened it and Taneční aktuality later published a short reflection. It’s good somebody writes about this topic; however, I would like to share my own view. I must point out that the “unprepared, unconfident and inexperienced graduates of Czech conservatories”, as it has been formulated, have grown into outstanding personalities of Czechoslovak, Czech, European and world ballet, and not only into excellent dancers, but also choreographers, teachers, artistic directors of ballet companies, theatre directors, managers, costume designers. physiotherapists and others. Sure, they started as immature and inexperienced artists, but they succeeded because somebody trained them during the first years of their engagement. That is often neglected now. I understand the selection of new members is determined by the company’s scope and repertory, for instance, they need to hire soloists for some roles. But I don’t understand why talented graduates are not admitted as corps de ballet members and why nobody works with them. Experience can only be gained through hard work.

But out of three hundred people arriving at auditions, as a company director you eventually pick those who have ideal dispositions and fit in the company. Maybe we should ask if company directors see any vocation in what they do and if they have ambitions to “bring up” a Czech dancer when there are so many to choose from…

In my opinion, Czech companies don’t need to employ so many international dancers. When I go to see a performance, they don’t seem to be so much better. This year we’ve had a very strong graduating class – if it was admitted to a theatre as one group, they would have the potential to form a top-quality and compact ensemble (Laurette Hrdinová did this in the past when she took one whole class of graduates to Ústí nad Labem.). I know it’s not even possible today, but I believe they are talented young people and I’m happy to see they have found their place in different companies or at universities. For example, Kristián Pokorný, who is, in my opinion, a highly talented and promising young man, has started a career in Mannheim. I think he could be at the National Theatre and develop his career here. Pavlína Kopecká, who had an opportunity to become a demi-soloist in Brno right after school, has been offered a contract with the Czech National Ballet and she has chosen Prague. It’s a girl with a great potential so I hope she will use it well. It’s important to be in the right place at the right time.

Do your students seek your advice when deciding about their future, about auditions or contracts?

Sometimes they ask me, but I don’t want to give them any concrete advice, everybody must decide for themselves. I just tell them to consider where they are really wanted. It’s always better than joining a company who needs them just to fix the number of dancers.

Obviously, you have been lucky enough - you have danced tens of roles, not only in the National Theatre. Is there any ballet you have a special relation to?

Recently I’ve realised that I’d done 84 roles, not including guest performances. But it’s history, I think nobody is interested in it now, nor in the stories about my studies and my early career…

I don’t think so – I love to talk about the past.

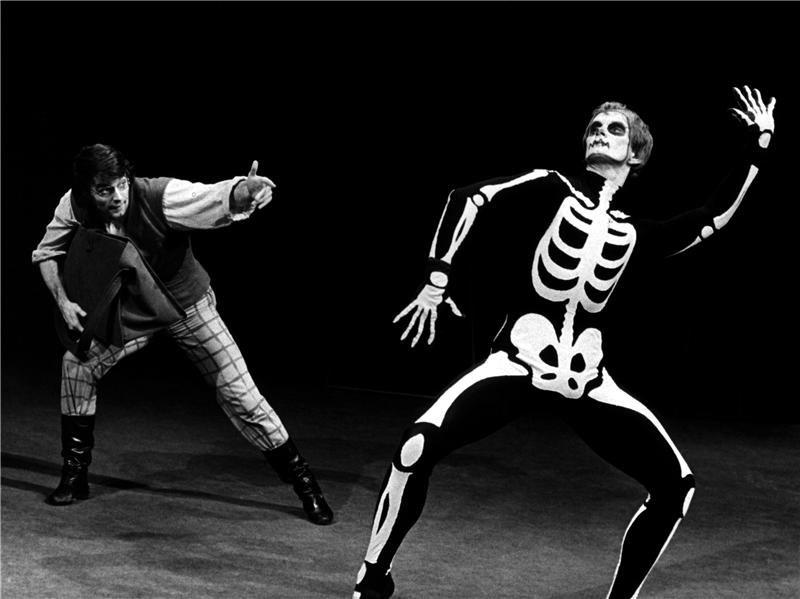

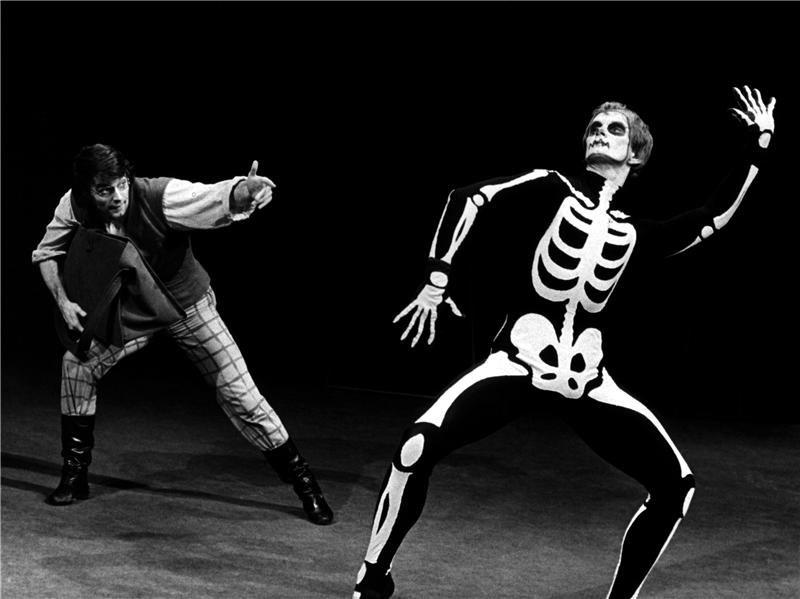

It’s been fifty years since my first performance in the National Theatre and I’ve been teaching at the Conservatory for forty-five years. Mentally, I don’t feel to be 70, though physically I feel I’m not twenty any more (laugh). Sometimes I have problems getting up and it takes some time to get my body moving. I danced my very first show on 12 September on the day of my 20th birthday. It was an Othello by Jan Hanuš, choreographed by Jiří Němeček, with sets designed by Josef Svoboda. I danced the five couples. Othello was staged twice. The first version was the first ballet I had even seen. I remember we went to the theatre with my aunt, who is now 98, and I was already dancing in Poděbrady. We travelled to Prague, sat on the second gallery and the tickets cost 3 Czech crowns each. When I started to attend the preparatory course, I danced a page in the same Othello. In the second version, I debuted as an adult dancer. It was probably the ballet of my life. But do you know what is worst about those fifty years in dance industry? That there have been the same problems all the time – and nothing really changes, on the contrary, it gets worse.

What problems are the most serious?

What problems are the most serious?

It’s mainly the malice inside the dance field, intolerance, disrespect to each other’s work which harms the whole field. I remember we had an appointment with the deputy minister of culture, we were there with Zdeněk Prokeš on behalf of the Dance Association of the Czech Republic’ Board and we discussed social security for dancers. And they told us: “First, you should discuss it among yourselves.” Since they had spoken to somebody who had presented a totally different views and requirements than we did, it was very confusing. And that’s true – we haven’t managed to create any dance lobby that would deal with the essential issues of the dance field. I remember when the National Theatre badmouthed Šmok and Ogoun, and they badmouthed it back, for no reason. Such things don’t happen in music, musicians are able to stand by each other, we are not. Can you imagine a dance festival that would embrace all dance genres and the field in all its extensity? In music it’s possible, music festivals feature great classics, symphonies, one day you can listen to Bernstein, the next day you attend a jazz evening or contemporary opera… there’s no dance festival that would include all kinds of dance productions. Classics and original new works can be presented side by side, anyway.

Do you believe in constant values in dance?

Definitely. They are in music, in opera, and nobody impeach them because they know they would make themselves look stupid. Classical dance is based on high aesthetic values, and not everybody approves of them but it’s their problem, the works still alive after 100 years and all the changes cannot be blamed. After all, classical ballet titles are always sold out. In this season I’m supposed to stage The Sleeping Beauty in the South Bohemia Theatre with a premiere in May and people are already asking about tickets. I don’t say we should only stage traditional titles, but we cannot reject them. Besides the classics, there are original contemporary creations that will eventually turn into constant values. For example, Kylián or Forsyth are rated among modern classics, and new works are being created. Petipa wasn’t always a genius. either, he did many things that have been forgotten…

Let’s get back to the problems of the dance field….

All the insecurity and inability of self-defence and self-presentation results in missing many new talents, because the dance profession is not something all our society would support. The space it is granted in media is almost zero. Recently, somebody has commented on the normalisation period, on the terrible situation in theatres that presented almost exclusively ballet titles. He pronounced it with such disrespect, as if ballet was some inferior form of art. On the day of the Thalia Award ceremony, Aleš Cibulka invited some of the nominees on his Czech Radio programme and dance wasn’t even mentioned, as if the category didn’t exist. After the awards were handed out, the situation in media was very similar and open letter was sent to the Czech Television. I feel there’s still not enough support from the Czech Television. As a public medium it should give space to dance, and do it on a regular basis, if possible, so that viewers get used it. Only television can do something for dance, because it is visual art and it can attract viewers via TV screens.

To conclude, do you think that as a dancer you were lucky to be surrounded by good directors and choreographers? Did you have a fulfilling career?

If it hadn’t been fulfilling I couldn’t have done it for fifty years. Dance is an ephemeral art. A performance ends and everything is over. A poem or a music score can rest in a locker for thirty years and be rediscovered and published with all the pomp. In dance you must grab attention now, in this very moment, or never. It depends largely on a director and a choreographer. They determine your career. I’ve known talented choreographers who never got an opportunity, or they got one that was far too big for their abilities. But I know that working with people is extremely hard and responsibility can’t be turned over to somebody else.

What should be dancers prepared for?

They should be prepared for a professional life that is hard – mentally, emotionally, and physically. It’s important to be strong, to overcome many things, to not let yourself be discouraged and go on. I know many people who were working hard and doing what they were asked for and so they deserved to be given a chance. It might take some time. But I believe that hard work always pays off.

Jaroslav Slavický (born 12 September 1948)

After graduating from the dance department of the Prague Conservatory (1967) he studied at the Vaganova Academy in Leningrad. In 1968 he joined the National Theatre Ballet, later he became a soloist in the Théâtre Municipal Strasbourg (1967/1970) and Stadttheatre Basel (1970-1972). In 1972 he returned to the National Theatre where he was a soloist, from 1975 the first soloist and during 1990-1998 he worked as a ballet master and teacher. On the stage of the National Theatre he created around 80 roles and solo parts (among others, it was the Prince and Rottbart in Swan Lake, Albert in Giselle, Romeo and Mercucio in Romeo and Juliette, Prince in The Sleeping Beauty, Crassus in Spartacus, Adam in Stvoření světa. Faust and Satan in Doctor Faustus). As a choreographer and ballet master, he participated in many productions of the National Theatre (Swan Lake, Don Quixote, The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle, The Wayward Daughter/Polovtsian Dances, Choreography from the Netherlands, Americana and others.)

From 1972 he taught classical dance and stage/performance practice at the Dance Conservatory of the City of Prague, in 1987 he graduated in Dance Pedagogy at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, in 1987-1996 he worked as a teacher there. Since 1996 he has been the head of Dance Conservatory of the City of Prague, and he is the founder of the associated ballet company Bohemia Ballet. For the Conservatory, he has staged ballets such as The Nutcracker, Polovtsian Dances and The Sleeping Beauty. For the Brno National Theatre ballet ensemble, he staged Don Quixote (1996), the Czech premiere of La Bayadère (2003, 2013) and Raymonda (2008). For the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre he prepared The Nutcracker in 2001. He has collaborated with Theatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro (The Sleeping Beauty, 1998, 2005). He helped to stage Don Quixote in Bädische Staatstheater in Karlsruhe (2004), the State Opera in Prague (2012) and the National Opera in Bucharest (2012). With the National Theatre Ballet, he has toured many European countries, as well as Cuba and Canada. In 1988-1992 he was an artistic advisor of the Newfoundland and Labrador Ballet Canada. He has taught ballet classes in Bordeax, Edinburgh, Rio de Janeiro, in Bloomington (USA) in Columbia, Japan etc. and he has been a member of international juries at a number of ballet contests.