Miřenka, you wrote a novel. It's fiction, it's literature, yet a lot of negative reactions have come to you from the core of the dance field. What do you think is the reason behind it?

Imagine someone writing a novel from a medical environment. What would happen? Would doctors revolt and say, „It isn’t like that!“ ? I don't think so. While a field that is experiencing many upheavals, in which old dogmas cease to apply, is naturally hypersensitive when being criticised. There is some frustration, anxiety or stress under the surface, whether from an economic point of view or out of concern for one's own health and uncertain future. And also the fear that if something happens, no one will take care of you, you will not receive support that will help overcome difficult times or give the possibility of further growth. By the way, this is what the Dance Career Endowment Fund is trying to do, which I am watching and acknowledging, because I think it is necessary and very much needed. These activities should emancipate the industry, because permanent uncertainties can be frustrating. Perhaps this is the source of that particular stress and low self-esteem. And thus, the inability of any distance and hyperbole, as well as the acceptance of a different view. I think the worst thing is to nod in agreement with those who have the power to decide for us, because it is the plurality of opinions that creates a living, democratic, rampant and inspiring environment. It is necessary to learn to respect a different opinion, to respect criticism, to respect even the weaker ones, those who do not currently have power.

Was studying at the conservatoire really that terrible?

Everyone says terrible, but I don't mention that word anywhere. I aim at very specific things and try not to generalize. Basically, I can't identify with spitting on ballet. If the problem is not named, it will not be fixed. It's the same with the crisis. If we all nod in agreement, there will be no critical insight and we will remain silent. And I think the biggest mistake is not to express oneself, and then to complain in ballet locker rooms and create a completely different picture in public.

Let's get to your writing now. In Ballet Dancers, the protagonist publishes a secret school magazine, which immediately raised the question in me, whether it is a parallel from your life and whether the birth of your future writing manifested itself here?

It is true. And the truth also is that I was temporarily expelled from school for my first literary ambition!

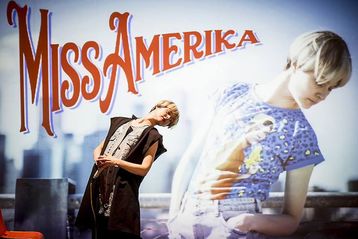

So that's where it started, and your literary first is Miss AmeriKa?

No, I wrote a set of short stories Goodbye, Turnier!, which was unofficially published by HAMU (The Music and Dance Faculty of the Academy of Arts Prague). I tended to write, but I probably never took it seriously enough to find the time for it. For Goodbye, Tournier! I did a show of the same name. It was about a writer and in terms of genre it was a physical and movement theatre. I was still in my third year at HAMU. I worked on certain phases of writing: from the initial thought, the impulse, through doubts, the struggle with my own alter ego, when my own "I" is a little different, when fiction comes and when it influences reality. That is already happening to me with Ballet Dancers as well. I'm actually starting to think about different passages, whether it really happened, or I made it up. And I'm not so sure anymore.

What was the turning point in taking the time to write?

Ballet Dancers were created during my maternity leave. The book’s editor Ondřej Nezbeda told me: „You have to write it before the child starts walking.“ But I didn't know when children could start walking, so I wrote it faster. I parked the stroller behind the cafe window, sat down, and wrote. And it went fast, in fact it saved me from the shock of being a mother. I wasn't ready for it and I needed something of my own. What I like most about that book is that some things are unsaid, just like in dance. The book is breathing. It lives its own life. It was similar with Miss AmeriKa. When I finished my work for the Czech Center in New York as a program director, I stayed there for another six months because I wanted to do things I didn't have time for. For example, I went to a stand-up comedy course, workshops and contemporary dance lessons, I also directed and started working on Miss AmeriKa. And there I made sure I could sit on my ass and write.

But your work otherwise develops directly on stage and is created by movement and experience of the body, isn't it?

Not quite, I actually write all the solo performances in advance. I'm writing sort of a movie script. I have boxes and I write about what is happening in space, what is happening in the sound, in the projection, what the significance is to be and, of course, other added components. So, I have a structure and it gives me freedom. In addition, this system allows me to work as a director and performer at the same time. Because otherwise it's very complicated. If I have to improvise, I need someone to give me feedback from the outside. When I have a solid structure, I carry my imagination in my head and I know where I want to go from, so I can afford to loosen inside that structure without losing its meaning. The significance for me exceeds the purely aesthetic component. For me, the primary is the concept and meaning.

I've always been fascinated by the way you work. I don't know if you always have it that way, but at least lately I've been feeling an honest research in your work, which has several components of preparation, be it text, film or documentary. That's how I think few people work. Is it a process you came up with, or did you learn it somewhere?

I don't know if it's honest work. Equally honest work is when someone is in the studio devoting x hours of movement to prepare a performance. For me, it's the intellectual work I need to create before the work is created. I have to have a serious reason why I want to get on stage, I can't do something that isn't absolutely necessary for me. The process is so painful and demanding that I have to go for everything, otherwise there is no point in doing it. That is why all my performances are based on some personal, essential themes that come to me in the current world. By beginning to address them on a broad scale, they become universally valid. For example, S/He is Nancy Joe came about in such a way that I needed to deal with the fact that my brother was not a brother, but a sister. For a year and a half, I studied the topic from a medical point of view to personal penetration into the trans community. I need to know the topic in depth and from many sides so that I can bring it to the stage. For me, a personal feeling is not enough. But that's my way, it doesn't have to be for everyone at all. But I have to know that I have come deep, that I will not draw any more, that I have done my best for this topic. But of course, each form, each genre requires a slightly different approach. Sarah Kaufman of the Washington Post wrote about me that what I do is „docudance“ - like a documentary dance - and I actually like that as a label for my work.

If I were to ask you about the good qualities that studying at the conservatoire have given you in your personal and professional life, what would it be?

Well, maybe I'm a workaholic: the more you work, the better! Although I don't really know if it's completely positive. As is well known, a lot of creative things come from procrastination. The moment a person lies in a hammock and can relax, he loses his clutter and just contemplates, the greatest things arise even in science, everywhere. Jung was building with stones, Einstein was lying under a tree, and I have perhaps the most inspiration when I take a shower. So workaholism, which is overrated in our society and is a symptom of economic thinking, is not really that positive. But the workaholism created from that hard work helped me graduate from two colleges at once, get a doctorate, and lead two companies. It's actually an awful lot of things that I did in a short period of time because I was trained. But maybe I also have great musicality, things related to music go very well for me, I can guide actors in melodrama and opera. I communicate with the composer about my performances and I know exactly what music I want. From the studies, I also carry the romantic gesture, the soaring desire for beauty - not physical, but aesthetic. When you imagine an open hand gesture, you inhale and extend your hand another millimeter… At that moment, as if the whole being had risen… It brings euphoria. I experienced that little in ballet, I experienced it more in my later work, but ballet taught me that. That's what attracted me. Such liberation from oneself.

I perceive you as a Renaissance creature, you master a lot of genres. What role do you feel best in?

I don't think it matters. Everything comes from the same place: running away to solitude. Writing is most introverted. In contrast, directing requires communication and the transmission of ideas. And when I'm alone on stage, it's connected there. My primary concern is to be free in everything I do. Freedom is a topic that school has imprinted on me, in the sense that I suffer from a lack of it. It is about freedom of the body, decision-making, destiny, direction, thoughts. I must feel that I have many options for which way to go. In America, the word dancemaker is now used for a choreographer, merging the roles of choreographer and dancer. And I say about myself that I'm a performance maker because I do performative things. Even the book is performative in a way. And one more thing: in the word maker, I feel that one really has work hard. With their own feet and hands.

Miřenka Čechová is a contemporary Czech representative of dance and physical theater, director, writer and pedagogue. She co-founded the theater group Tantehorse and also the artistic group Spitfire Company. She began her career studying classical ballet at the Dance Conservatoire in Prague. After graduating, she graduated in parallel from DAMU (alternative theater) and HAMU (non-verbal theater), where in 2012 she defended her doctorate in directing physical and mime theater. During her studies, she received a prestigious Fulbright scholarship for research and teaching at American University in Washington, DC, where she was the first to teach physical theater. She is the author of several dozen feature productions, whether in the position of author and performer or director. She lectures at Czech and foreign universities and has won a number of Czech and international awards, such as S / He is Nancy Joe (The Best of Contemporary Dance 2012 by Washington Post, Herald Angel Award at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival), The Voice of Anne Frank (Best of Overseas Production at the International Arts Festival in South Africa, Outstanding Performance Award at the Prague Fringe Festival, Best of Fringe at the Amsterdam Fringe Festival), Antiwords (Theater Newspaper Award, Next Wave Festival Award, Skupova Plzen Award) and many more. In recent years, she has also written two books - Miss AmeriKa (2018) and Ballet Dancers (2020).

Her latest projects include:

TanteLab - Family Therapy - an educational art platform focusing on bridging the end of studies and professional careers for graduates of dance, movement and acting disciplines. Emergency Dances (Tantehorse) - dance and activism. Engaged work in the field of dance. For active creators who are looking for a dialogue with an overlap. The third series will take place in November 2020.

The production Skořápka - classical drama, Petr Bezruč Theater, dramatization and co-direction. The premiere will be in January 2021.

Documentary autobiographical series Invisible I./Hannah - premiere September 7, 2020 in the Akropolis Palace. The first part of a planned trilogy dealing with the fate of women artists doomed to disappearance. The first part with Hana Frejková, whose father was executed in a trial with Slánský.

Translated by Kristina Soukupová.