Chaplin in the Dream World of Mario Schroeder

Doubts. Questions. And curiosity. Such were my first reactions to the news that among the new productions of the ballet season in Ostrava there is a piece dedicated to one of the most famous figures in film history – Charlie Chaplin. The genius of the silent film era, inquisitive observer and connoisseur of human nature, creator of “the Tramp”, one of the most iconic movie characters of all time – and ballet? Is it possible to depict his complicated life full of dramatic twists, his complicated personality, reflected in a no less complicated approach to artistic creation, through dance? Can you imagine a less dance-like character than the Tramp with his funny waddling gait à la penguin, his head tics and a ridiculous walking stick? And after all, is the task of rendering the chaplinesque ridiculousness and dignity of a human being, facing the chaotic and often hard times not suitable rather for drama or pantomime?

German choreographer Mario Schroeder obviously holds a different opinion. Five years after the premiere of a production bearing the name of the “king” of film comedians on his home stage in Leipzig, he accepted an offer to mount this piece at the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava. And in the same breath I have to say that it was an exceptionally fortunate decision, which won the Ostrava ensemble a show that has become a true, royal gem in their repertoire.

As we learn from the program brochure, the German choreographer split the whole production into sixteen stage images set to the music by more or less known composers of the 19th and 20th centuries. These tableaux cover the most important moments of Chaplin's personal and artistic life – his childhood spent in poverty in London, his humble artistic beginnings, worldwide fame and public condemnation, and finally, his meeting with Oona O'Neill, who had been a support to him until the rest of his life. In most of these images Chaplin-the person shares the stage with his most famous screen persona – the Tramp, who brought him worldwide fame, but whom he had to leave behind with the advent of sound films.

Doubts. Questions. And curiosity. Such were my first reactions to the news that among the new productions of the ballet season in Ostrava there is a piece dedicated to one of the most famous figures in film history – Charlie Chaplin. The genius of the silent film era, inquisitive observer and connoisseur of human nature, creator of “the Tramp”, one of the most iconic movie characters of all time – and ballet? Is it possible to depict his complicated life full of dramatic twists, his complicated personality, reflected in a no less complicated approach to artistic creation, through dance? Can you imagine a less dance-like character than the Tramp with his funny waddling gait à la penguin, his head tics and a ridiculous walking stick? And after all, is the task of rendering the chaplinesque ridiculousness and dignity of a human being, facing the chaotic and often hard times not suitable rather for drama or pantomime?

German choreographer Mario Schroeder obviously holds a different opinion. Five years after the premiere of a production bearing the name of the “king” of film comedians on his home stage in Leipzig, he accepted an offer to mount this piece at the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava. And in the same breath I have to say that it was an exceptionally fortunate decision, which won the Ostrava ensemble a show that has become a true, royal gem in their repertoire.

As we learn from the program brochure, the German choreographer split the whole production into sixteen stage images set to the music by more or less known composers of the 19th and 20th centuries. These tableaux cover the most important moments of Chaplin's personal and artistic life – his childhood spent in poverty in London, his humble artistic beginnings, worldwide fame and public condemnation, and finally, his meeting with Oona O'Neill, who had been a support to him until the rest of his life. In most of these images Chaplin-the person shares the stage with his most famous screen persona – the Tramp, who brought him worldwide fame, but whom he had to leave behind with the advent of sound films.

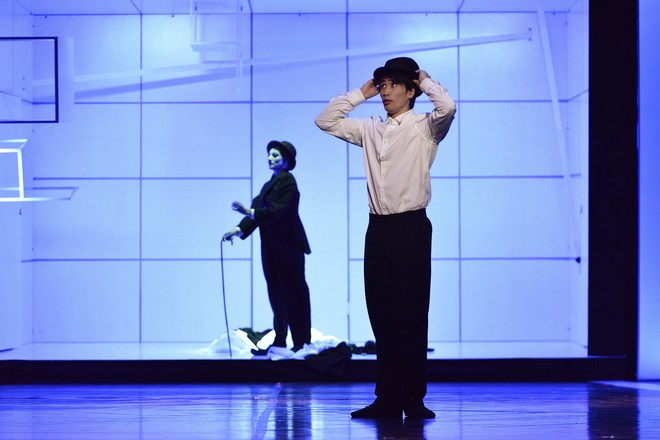

So much for the author's concept. What we see on the stage, however, leaves a very different impression. In no way is it a precisely defined sequence of chronologically arranged short scenes set to particular musical compositions, the only goal of which is to tell the story of the famous Englishman. Mario Schroeder is too refined and wise choreographer to be happy just with that. Instead, with the very first scene – sort of character exposure of the Tramp – he slowly ushers us into his chaplinesque world which, while still possessing both the external, Chaplin-like formal features and the Englishman's ubiquitous poetics of humor that walks hand in hand with the tragedy of modern man, has been unmistakably outlined by Schroeder. Indeed, he succeeded at the seemingly impossible – on the stage he created a strange, peculiar space-time, in which Chaplin is inherently present, yet it is not a mere imitation, but rather – one might say – an equal dialogue between two artists – an Englishman and a German, a filmmaker and a choreographer – across artistic genres and generations. The specific nature of Schroeder's approach is further supported by the fact that one can not prepare in advance for his view of Chaplin-the person and the artist, even the most painstaking study of Chaplin's life and work here provides nothing more than a hint, but everyone must find the key themselves. And it is not easy. If you focus from the very beginning just on the surface (and I dare say that probably most of those in the audience do), on a purely formal aspect of what you can see, on a searching game of the sort "find Chaplin in that", you remain helplessly stranded at the gates of Schroeder's world, deprived of any opportunity to enter. Fortunately, he offers a discreet, inconspicuous, yet tangible guidance, and that is – to start dreaming along with him. To get rid of any kind of prejudice, predetermined ideas or expectations and become fully immersed in his dream world, the poetics of which oscillates between elusive surrealistic images and harsh reality, which bears testimony to the negative aspects of human nature that left such a tragic imprint upon the history of the 20th century. After all, watching the charming scene from a Hollywood studio with actors in pink dressing gowns wearing masks of film stars of the day, who would mind such an unimportant detail that Steve McQueen definitely could not meet Chaplin there. Who would be puzzled by the fact that in the last scene we can see Chaplin, the Tramp and Oona, whom he met only six years after he had put his most famous screen persona to rest. And who would be shocked by the fact that Fred Karno, Chaplin's first impresario and the originator of modern slapstick comedy dances on the stage in the style of electric boogaloo. It all fades and pales in comparison with a single, utterly magnificent scene where from a pile of clothes, guided remotely by Chaplin's movements, the figure of the Tramp emerges for the first time and dances with its creator an intimate duet, in the course of which Chaplin leads it with his delicate touches and finishes its last nuances. And the fount of Schroeder's imagination and creativity is seemingly without end; Sometimes he works just with a completely empty stage with a few props and characters, such as in the scene depicting the advent of sound film. This is represented by a single giant microphone that emerges from the wings and hits the Tramp first and then Chaplin himself and which is – after a remarkable comical "fight" – eventually ousted from the scene.

So much for the author's concept. What we see on the stage, however, leaves a very different impression. In no way is it a precisely defined sequence of chronologically arranged short scenes set to particular musical compositions, the only goal of which is to tell the story of the famous Englishman. Mario Schroeder is too refined and wise choreographer to be happy just with that. Instead, with the very first scene – sort of character exposure of the Tramp – he slowly ushers us into his chaplinesque world which, while still possessing both the external, Chaplin-like formal features and the Englishman's ubiquitous poetics of humor that walks hand in hand with the tragedy of modern man, has been unmistakably outlined by Schroeder. Indeed, he succeeded at the seemingly impossible – on the stage he created a strange, peculiar space-time, in which Chaplin is inherently present, yet it is not a mere imitation, but rather – one might say – an equal dialogue between two artists – an Englishman and a German, a filmmaker and a choreographer – across artistic genres and generations. The specific nature of Schroeder's approach is further supported by the fact that one can not prepare in advance for his view of Chaplin-the person and the artist, even the most painstaking study of Chaplin's life and work here provides nothing more than a hint, but everyone must find the key themselves. And it is not easy. If you focus from the very beginning just on the surface (and I dare say that probably most of those in the audience do), on a purely formal aspect of what you can see, on a searching game of the sort "find Chaplin in that", you remain helplessly stranded at the gates of Schroeder's world, deprived of any opportunity to enter. Fortunately, he offers a discreet, inconspicuous, yet tangible guidance, and that is – to start dreaming along with him. To get rid of any kind of prejudice, predetermined ideas or expectations and become fully immersed in his dream world, the poetics of which oscillates between elusive surrealistic images and harsh reality, which bears testimony to the negative aspects of human nature that left such a tragic imprint upon the history of the 20th century. After all, watching the charming scene from a Hollywood studio with actors in pink dressing gowns wearing masks of film stars of the day, who would mind such an unimportant detail that Steve McQueen definitely could not meet Chaplin there. Who would be puzzled by the fact that in the last scene we can see Chaplin, the Tramp and Oona, whom he met only six years after he had put his most famous screen persona to rest. And who would be shocked by the fact that Fred Karno, Chaplin's first impresario and the originator of modern slapstick comedy dances on the stage in the style of electric boogaloo. It all fades and pales in comparison with a single, utterly magnificent scene where from a pile of clothes, guided remotely by Chaplin's movements, the figure of the Tramp emerges for the first time and dances with its creator an intimate duet, in the course of which Chaplin leads it with his delicate touches and finishes its last nuances. And the fount of Schroeder's imagination and creativity is seemingly without end; Sometimes he works just with a completely empty stage with a few props and characters, such as in the scene depicting the advent of sound film. This is represented by a single giant microphone that emerges from the wings and hits the Tramp first and then Chaplin himself and which is – after a remarkable comical "fight" – eventually ousted from the scene.

Almost surreal is the scene with the rise of the Dictator, who crawls between the two main protagonists in a giant inflatable balloon, from which he starts to hatch whilst shouting in a Hitler-like manner – an obvious allusion to the movie The Great Dictator. However, both the Dictator's globe-like balloon and his bloated ego are soon destroyed when Chaplin and the Tramp slyly and unexpectedly pierce it. In contrast to these almost intimate scenes, however, Schroeder occasionally lets his creative imagination run riot and populates the stage with a whirl of characters that show the whole range of Chaplin poetics and humor either in costumes, physical stylization or their play with props, all accompanied by a projection on the back screen and the audiences then have hard time indeed deciding what should they pay attention to first.

Almost surreal is the scene with the rise of the Dictator, who crawls between the two main protagonists in a giant inflatable balloon, from which he starts to hatch whilst shouting in a Hitler-like manner – an obvious allusion to the movie The Great Dictator. However, both the Dictator's globe-like balloon and his bloated ego are soon destroyed when Chaplin and the Tramp slyly and unexpectedly pierce it. In contrast to these almost intimate scenes, however, Schroeder occasionally lets his creative imagination run riot and populates the stage with a whirl of characters that show the whole range of Chaplin poetics and humor either in costumes, physical stylization or their play with props, all accompanied by a projection on the back screen and the audiences then have hard time indeed deciding what should they pay attention to first.

Speaking of physical stylization, it should be noted that Schroeder's movement vocabulary is partly based on the tradition of German Tanztheater, his clear-cut work with movement and thoroughness of corps de ballet scenes remind us of his mentor and former artistic director of the Leipzig Ballet, the late Uwe Scholz. Above all, however, he creates a distinctive movement vocabulary, in which all the aforementioned organically blends with elements of slapstick, breakdance and even electric boogaloo, which was performed by European champion in this discipline (and member of the corps de ballet) Patrick Ulman. Then there are three Femmes Fatales of Chaplin's life: Ayuki Nitta in the role of pretty, but somewhat shallow Mildred Harris, sensually seductive Barbora Šulcová as Paulette Goddard and childishly naive Oona O'Neill performed by Chiara Lo Piparo. The driving force behind the show and at the same time a kind of “camera lens”, through which we interpret all the action on stage are the two protagonists: Chaplin-the person and his cinematic alter ego – the Tramp. The former was performed by Koki Nishioka, whose dancing was technically proficient and physically precise, however, his interpretation of the role has left behind a big question mark. Contrary to the expressively dominant Tramp his Chaplin almost lacked any expression at all. It cannot be said that Nishioka did not attempt at his own interpretation of the character, or that he even danced without any enthusiasm, quite the contrary. Yet it looked as if he was constantly restrained by some kind of intangible, impenetrable barrier of emotional reticence that prevented him from getting any deeper, genuine emotion across the forestage to the auditorium. In contrast, Amelia Waller's performance as the Tramp was nothing short of phenomenal. In comparison with other performers it was quite obvious that while they were still exploring their characters, the Australian danseuse actually was the Tramp. It is beyond doubt that her undeniable stage experience and natural gift of expressiveness, together with her long experience with this role came in useful as well, but there was much more than that. All those perfectly acquired and performed chaplinesque movements and gestures, elaborate nuances in her means of expression, an omnipresent light touch of melancholy, tinging even the funniest moments – none of these was just an empty mannerism, but rather a form of her internal dialogue with the Tramp, who, compared to the original, was subtler, more delicate and sophisticated in conveying her expressive range, but no less convincing. Such an impeccable performance may ironically become a doom for her successors in this role, for whom, I am afraid, she has set the standard too high.

Speaking of physical stylization, it should be noted that Schroeder's movement vocabulary is partly based on the tradition of German Tanztheater, his clear-cut work with movement and thoroughness of corps de ballet scenes remind us of his mentor and former artistic director of the Leipzig Ballet, the late Uwe Scholz. Above all, however, he creates a distinctive movement vocabulary, in which all the aforementioned organically blends with elements of slapstick, breakdance and even electric boogaloo, which was performed by European champion in this discipline (and member of the corps de ballet) Patrick Ulman. Then there are three Femmes Fatales of Chaplin's life: Ayuki Nitta in the role of pretty, but somewhat shallow Mildred Harris, sensually seductive Barbora Šulcová as Paulette Goddard and childishly naive Oona O'Neill performed by Chiara Lo Piparo. The driving force behind the show and at the same time a kind of “camera lens”, through which we interpret all the action on stage are the two protagonists: Chaplin-the person and his cinematic alter ego – the Tramp. The former was performed by Koki Nishioka, whose dancing was technically proficient and physically precise, however, his interpretation of the role has left behind a big question mark. Contrary to the expressively dominant Tramp his Chaplin almost lacked any expression at all. It cannot be said that Nishioka did not attempt at his own interpretation of the character, or that he even danced without any enthusiasm, quite the contrary. Yet it looked as if he was constantly restrained by some kind of intangible, impenetrable barrier of emotional reticence that prevented him from getting any deeper, genuine emotion across the forestage to the auditorium. In contrast, Amelia Waller's performance as the Tramp was nothing short of phenomenal. In comparison with other performers it was quite obvious that while they were still exploring their characters, the Australian danseuse actually was the Tramp. It is beyond doubt that her undeniable stage experience and natural gift of expressiveness, together with her long experience with this role came in useful as well, but there was much more than that. All those perfectly acquired and performed chaplinesque movements and gestures, elaborate nuances in her means of expression, an omnipresent light touch of melancholy, tinging even the funniest moments – none of these was just an empty mannerism, but rather a form of her internal dialogue with the Tramp, who, compared to the original, was subtler, more delicate and sophisticated in conveying her expressive range, but no less convincing. Such an impeccable performance may ironically become a doom for her successors in this role, for whom, I am afraid, she has set the standard too high.

The staging of Chaplin in Ostrava ranks among the productions that are very difficult to convey in words, and even harder to review. Not because they are in any way formless, vague, bland, or lacking any thought-provoking points or moments. The reason lies elsewhere – Chaplin is so imbued with peculiar poetics and distinctive style, which mixes gentle lyricism with narrated reality into a fleeting, elusive entity that it is almost impossible to analyze the experience retrospectively. It is like getting lost in a web of dreams, where everything has its own logic and laws, and where with every revealed context, with each uncovered fiber of that web there is another one that leads somewhere away, further into the unknown. Actually, Chaplin said goodbye to his most famous screen persona in a similar way in the movie Modern Times (1936), which ends with the Tramp symbolically going away from the viewer towards the horizon. On the other hand, Schroeder's Tramp says goodbye to Chaplin and as the curtain slowly falls, he walks towards us, the audience, as if he was asking us to join him on his journey into the unknown. It would be a huge shame not to follow him.

Review of the second premiere held on November 21st, 2015 at the Jiří Myron Theatre in Ostrava.

The staging of Chaplin in Ostrava ranks among the productions that are very difficult to convey in words, and even harder to review. Not because they are in any way formless, vague, bland, or lacking any thought-provoking points or moments. The reason lies elsewhere – Chaplin is so imbued with peculiar poetics and distinctive style, which mixes gentle lyricism with narrated reality into a fleeting, elusive entity that it is almost impossible to analyze the experience retrospectively. It is like getting lost in a web of dreams, where everything has its own logic and laws, and where with every revealed context, with each uncovered fiber of that web there is another one that leads somewhere away, further into the unknown. Actually, Chaplin said goodbye to his most famous screen persona in a similar way in the movie Modern Times (1936), which ends with the Tramp symbolically going away from the viewer towards the horizon. On the other hand, Schroeder's Tramp says goodbye to Chaplin and as the curtain slowly falls, he walks towards us, the audience, as if he was asking us to join him on his journey into the unknown. It would be a huge shame not to follow him.

Review of the second premiere held on November 21st, 2015 at the Jiří Myron Theatre in Ostrava.

Chaplin Concept and choreography: Mario Schroeder Sets and costumes: Paul Zoller Lighting design: Daniel Tesař

Translation: Tomáš Valníček