QUESTIONABLE BPM GASPING FOR BREATH…

In early April, the Czech National Ballet presented this season’s last premiere bpm. The abbreviation should stand for beats per minute, which is a term referring to the heart rate or rhythm of a music piece. Rhythm moves our bodies, which are – vice versa – influenced by the heart rate. We can provoke it to the extreme or we can calm it down in a slow motion. It is a pounding heart that connects all of us and this may be the reason why the production team opted for this title – human beings and their world became the topic that brings together all three parts of the evening.

When the management of the National Theatre announced the line-up for the evening, many people were stunned in surprise with the dramaturgy. Apart from famous Israeli names of Sharon Eyal, Gai Behar, and Eyal Dadon, who have worked for famous Batsheva Dance Company and Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, the program also featured Yemi A.D., the Czech multidisciplinary artist, choreographer, and dancer, whose focus is rather commercial. The professionals have been criticizing the head of the company Filip Barankiewicz for a long time for (among other things) not being familiar with Czech dance and ignoring it. The questions asked were, for instance, why famous Czech choreographers do not work with the Czech National Ballet. Most people were thinking about Lenka Vagnerová, Jana Burkiewiczová, Miřenka Čechová, Václav Kuneš or Viliam Dočolomanský if there was a desire for a big experiment. However, the head of the company interpreted the criticisms his way and everybody was curious about what the cooperation will result in. The fusion of various genres in big companies is nothing innovatory after all, mutual enrichment may be fruitful and bring a refreshing repertoire.

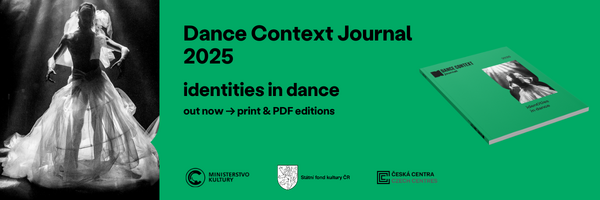

The evening starts and ends with the Israeli artists; it opens with Artza, the choreography by Eyal Dadon and his associate Tamar Barlev. The title in Hebrew stands for the commands in the dog training and the authors say it is truly rude to use it when speaking to another person. Figuratively speaking, Dadon contemplates the boundaries between freedom of expression and obedience, the inner contradiction between organic nature and artificial rules of the world in which a person is born. This is the reason why the main stage ingredient is a clear clash between two antipoles or civilizations – the first one living in harmony with the natural state of things and the other one that is strictly hierarchized and requires keeping the strict uniform rules. We could also see the action on the stage as an inner struggle within one person, a fight between natural behavior and education, a Freudian discrepancy between our instincts and societal rules, which the choreographer employs to impose the topic on each of us.

Dadon accentuates the untouched part of our personality and subliminally sends a critical message about the state of the world today similar to the laced-up part in black suits and white shirts. As a choreographer, he manages to be minimalistic but his dance echoes in all spatial relations, inside and outside dancers’ bodies. He sometimes brings the performers downstage where the audience can nearly touch them – a rather unexpected and refreshing method in big theatres. His dance gives an unrestrained and boisterous impression, even though the storm of energy usually does not overcome the virtual barrier between performers and the audience. Everything seems to be sterile and distant, the tsunami of emotions does not happen even though the energy invested in choreography and interpretation is more than visible.

The author often employs verbatim interpretation that is not typical for dance. Whether it is an implied cage that stretches along the stage or an insinuated dog train on metal chains that appears for a short time only to disappear again. Other props include the head mask of a wolf or a whip used to express the superiority of one class over another. The problem with the verbatim interpretation is that dance as such is not like that and it actually cannot be. It does not express itself as literally as words do but uses motion with multiple layers of meaning. It is clear then that any attempts to entangle the body in the net of defined meanings are doomed to failure and this may be the reason why Artza gave me an embarrassing impression. On the one hand, we can observe the traditional Israeli hallmark, extreme demands for the performance, and looking for original forms. On the other hand, it is only about being on the surface, shallowness, and uncertainty.

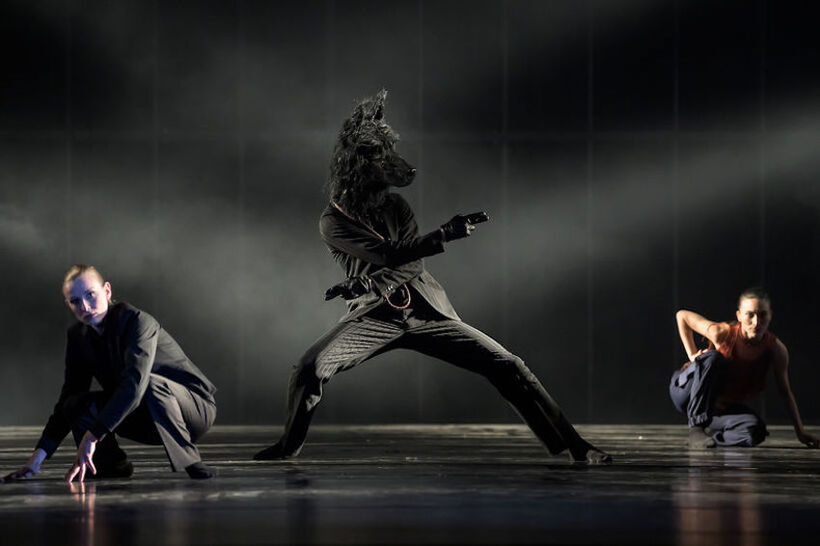

After the short interval, there was the time for Yemi A.D.’s Bohemian Gravity / Searching for Freedom. The topic of freedom and searching for one’s own way is a unifying topic for the first two pieces, although each author approaches the challenge in his own way. The author of the second piece distinguishes between gravity as a defining power shaping human nature and bohemian gravity that is supposed to draw us to “our primary journey”. It was then up to the piece and viewers’ wits to figure out the real meanings.

The choreographer sees Jakub Rašek as the main hero, who symbolically fights gravity most of the time. Other people in the company complete the scenes, carry the hero, run with him, and get lost in the imaginary labyrinth of life at the end of which he could be able to find the liberation from limiting freedom. Eliška Sky’s impressive stage design is dominated by a huge circular construction. The sides are made up of light that interacts with the performer or the other way round. The circles multiply and we may see them as layers of one reality. The costumes were designed by famous Czech designer Liběna Rochová and the music was composed by a producer and DJ known as NobodyListen. The interesting group of creators of Bohemian Gravity attracts attention and it is something we have not seen at the National Theatre so far. But… the anticipated miracle did not happen.

I consider Filip Barankiewicz’s idea so risky that it reminds me of Russian roulette. Although Yemi A.D. is an acknowledged artist in commercial art, after the new performance it is absolutely clear that he does not know his way around professional artistic dance and had no one to help him with getting familiar with it. After all, the program tells us that it is his first theatre production – at the National Theatre. Needless to say that not many people can manage to do that…

His choreography screams with deafening shallowness and the search for spectacular glitz. He is happy with superficial solutions dominated by ideas that are hardly original, such as the weird and clumsy casting of white cloth on the stage, which is lifted after a short time of imprinting faces, and the clumsy carrying of the hero. Another example may be Jakub Rašek’s run around the installation only to catch the rotating light. However, the light gradually catches up with him, he continues running heartbreakingly, accompanied by the music that would be perfect in a Hollywood movie. Swirling of the corps de ballet seems to be familiar as the performers keep alleviating the centripetal circles and stop in the middle to create a sculptural pose. I have no intention to upset anyone but I have seen the latest solution at amateur showcases of dance so many times I can hardly count. Yet in Bohemian Gravity it is the Czech National Ballet dancing!

The actions on stage are on the verge of kitsch, especially in the improvised part (at least it looked like it is improvised) when the task was “show whatever you can” This is the moment when everybody swishes their legs to their heads, do demanding jumps from classical dance technique, their pace is accelerating and they show everything. The icing on the cake is one of the last scenes, in which the style transforms into the famous vogue. It is probably one of the announced style fusions, in which the dancers were supposed to find their freedom… I have been wondering to which extent professional dancers have to master an immensely diversified motion offer? Good dancers are said to be able to dance anything. However, a question arises about whether it is real. Is it real to make dancers perform in The Swan Lake, Jiří Kylián’s pieces, Dadon Eyal’s work, and the vogue style?

My disappointment was dispelled by the last Czech premiere of the evening: Sharon Eyal’s and Gai Behar’s Bill. Their dance vocabulary literally throbs with energy and dominates the stage of the National Theatre. The dancers do not stop and their performances are of brilliant quality and dizzying speed. It is underpinned by Ori Lichtik’s and Oren Barzilay’s unstoppable and mesmeric techno beat that draws the frantic pace to the maximum. Unisono foreshadows how choreographers see society – the same, yet a different one. We can see various motion divergences, personal inputs of the performers, and the systematic infringement of the choreographic composition. After all, Sharon Eyal says: “The same timing, same shape, same idea, same style… but the absolute difference at the same time.” This ironic contrast became the leitmotif of the last part of bpm.

In Bill, dance is detailed and sophisticated, it often surprises us with unexpected solutions to situations, constantly trying to keep the audience’s attention. The authors systematically work with repetitive motion patterns, weaving the layers of the work. It is minimalism in perfection, creating an imaginary counterpoint to the spatiality of the first work of the evening. Watching this journey of high abstraction can become an extremely ecstatic experience. The constant layering of repetitions may appear problematic after some time. If your attention is drawn somewhere else, it is easy to get lost. Bill requires total concentration and immersion, which I did not manage to achieve. Although I was not absorbed by the work, I appreciate Eyal’s and Behar’s choreography that saves the precarious evening with bpm.

Finally, I – like a few colleagues before – must once again ask the question: who does dramaturgy of the Czech National Ballet? I assume that the person or team does very poor work and it is time to do something with it. For the past few years, we have heard so much criticism of the management of the ballet that it would cause the resignation of the director if it happened somewhere else. When will the top management of the National Theatre notice that Filip Barankiewicz and the company are heading towards mediocrity rather than a worldwide reputation? It is great we have excellent performers but what is the point when we cannot use the potential? The question is whether the management will notice and does not intentionally ignore the issue, since the contract for Barankiewicz has been recently prolonged for another five years. It is a truly pathetic show.

Written at the re-run on 6 April 2022, National Theatre.

Artza

Choreography and concept: Eyal Dadon

Co-author: Tamar Barlev

Music: Eyal Dadon, Nicolas Jaar, Daler Mehndi

Set: Eyal Dadon

Costumes: Bregje van Balen

Light design: Daniel Tesař

Dramaturgy: Liran Michaeli

Ballet masters: Jan Kodet, Miho Ogimoto

Bohemian Gravity: Searching for Freedom

Choreography: Yemi A.D.

Music: NobodyListen

Orchestra arrangement: Jan Šikl

Main assistant to the choreographer: Tomáš TOMMY Pražák

Assistants to the choreographer: Michaela Kadlčíková, Anastasiya Piatrenka, Tomáš Böckl

Set: Eliška Sky

Ligh design: Eliška Sky, Lunchmeat Studio, Daniel Tesař

Costumes: Liběna Rochová

Ballet masters: Alexandre Katsapov, Jiří Kodym

Bill

Choreography and costumes: Sharon Eyal, Gai Behar

Hudba: Ori Lichtik, Oren Barzilay

Production: Mariko Kakizaki

Light design: Avi Yona Bueno (Bambi)

Ballet master: Alexey Afanasiev, Radek Vrátil

Translation: Eliška Špilarová